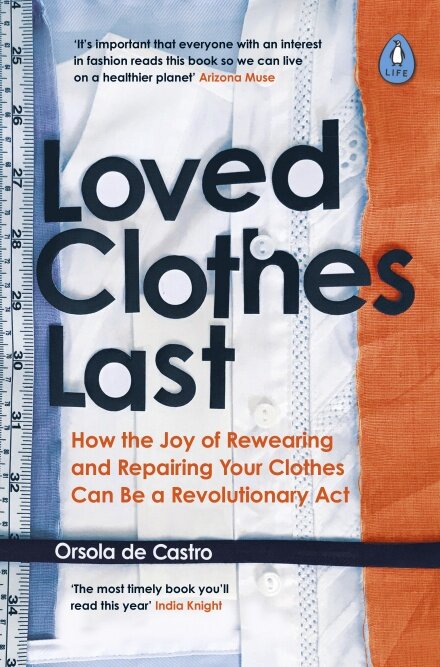

A chat with Orsola de Castro About : sharing clothes, Fashion Revolution & her new book –”Loved Clothes Last”

I used to wonder why the UK seemed so far ahead of the US in terms of awareness about the negative impact of the fashion industry on the planet but recently I discovered –at least in part– the answer: Orsola de Castro. No doubt, she would likely cringe from this assessment but blame the fact that I’m American and we’re known for exaggeration and over stating things. Regardless, I think it’s true.

Orsola is perhaps best known for being the CEO and cofounder of Fashion Revolution – which she would probably argue is the reason the UK has so much awareness that I previously mentioned. And I wouldn’t disagree. Her background, as an upcycling designer and creative thinker set her up to be who she is. Along with the fact that she grew up privileged and with/around amazing fashion. She’s recently written a brilliant book, Loved Clothes Last –more on that here– and graced me with her presence in a lovely Zoom interview.

Katya – Tell us a bit about Fashion Revolution.

Orsola – Well, we’re a global movement we started in 2013 as a result of the Rana Plaza disaster* and it’s very much globally centered on everyone’s voices. So though we run it from the UK, our country coordinators and our network of people is hugely important in the way that we speak.

Workers participating in a Fashion Revolution #whomademyclothes campaign

We focused on a pro-fashion campaign in the sense that we didn’t come from the negative and shaming attitude that other NGOs had. And we have grown to become the biggest fashion advocacy movement, activism movement in the world and we have a presence in over 90 countries.

We’re not so big in the United States but we have lots of little regional coordinators who actually work brilliantly and do really amazing projects so you’ll find one close to you. We work on a 360 degree vision which encompasses transparency and public disclosure, the toxic implication of working and using clothes that are drenched in chemicals and other aspects less known about fashion. We talk about the fashion industry as a whole –we don’t necessarily make a distinction about fast fashion and mass-produced luxury and we talk a lot about the inequalities and the inter-connectedness in between looking at it from a social point of view and an environmental point of view –the fact that you cannot separate people and planet. That both are exploited by a system and both need to be addressed for a better future.

How do we share this with people without overwhelming them?

I don’t think we’re at that stage anymore. I think that people are more ready to be overwhelmed than they were before. I mean we certainly started with the “no overwhelming thing” and it was very much about bringing people on a journey, make it joyous, make it collaborative, make it empowering so you felt that you were doing something with your actions. Whether these actions were about treating your clothes differently, buying differently, or activating on a more personal activism level such as petitions, or asking questions of the brands but I feel that now particularly after the pandemic, and after Black Lives Matter and after the environmental crisis that we are all going through that awareness has been raised and so what we need to do now is really work on that connection. People have made that connection with food and now we need to work harder to make people make the connection with clothes.

Yes, I completely agree that the locavore and organic food movements can give us road maps for looking at fashion. But tell me about the book which we’re so excited to read. Why did you decide to do a book?

I actually wasn’t planning on writing a book! I was picked on Instagram by the oldest literary agency in the UK, by someone I love deeply called Kate and to whom I nearly didn’t reply to because it was a DM and she wrote to me saying “I’d like to do a book on mending and I’m looking for someone to do a book on mending” and I replied saying “Well I’m really bad at mending actually. I could do you a kind of ‘how to mend’ but I would be really happy to do a ‘why to mend.’”

“I could write a book about how we need to think differently around mending clothes and mending systems, repairing things in our wardrobe and repairing damage that was done to people and to planet.”

So that’s the book I wanted to write and she agreed. So that’s the story.

And I love the title, Loved Clothes Last

Thank you. Well, Loved Clothes Last was a phrase way before it became a hashtag. It’s how I described my design process when I had my brand From Somewhere because we used to reuse – I had a lot of second-hand clothing so we reused mine and then we went on and used tons and tons of pre-consumer luxury waste. But it was something that I used to describe my way of working and my process.

And then with Fashion Revolution, we used it as the hashtag. That was our entry point into the environment element. Because before #lovedclotheslast we were #whomademyclothes and at that time we were just looking at the impact of the supply chain on workers –we were all about transparency and when #LovedClothesLast came, we took the concept of waste as our entry into a whole new conversation. We partnered with Greenpeace, we did a fanzine of lovedclotheslast. I have to say, I’ve been really proud to see this phrase that has been kind of swimming in my brain for the past 20+ years become a whole movement. Because it is a whole movement. I see it way beyond us –in many places.

Yes! We even created a set of videos and put that on the end as a tag before realizing it was from Fashion Revolution –though loved the connection when we realized it! Pre-Covid, another thing that was happening were clothing swaps but I’ve read that sharing clothes is a big part of your family tradition.

Sharing and reusing clothes is something that we’ve been doing for millenia. The fruit of poverty –but in the case of my family it wasn’t poverty because I come from a privileged family, after all, but certainly a family with sense and intelligence and when I was growing up my clothes weren’t “mine”; they would’ve been passed on from someone else.

My elder cousin’s clothes weren’t “hers”. They were something she would wear for a period, pass on to her sister, her other sister and then me as their cousin – because I had brothers –and I also inherited all of my brother’s shirts, trousers, jumpers and so on. But we do this thing at Chirstmas that for the book I coined Christmas Shedding. It actually didn’t have a name before but it’s very natural to us. Instead of –or on top of– shopping we share things that belong to ourselves but things that we love.

For example, if I know that someone has wanted something of mine for a while, I’ll give it to them for Christmas. Or I will wear something and then realize, Okay this is something I adore deeply but would look a hell of a lot better on my daughter. And this goes on and with my cousins, we have been sharing clothes for over 50 years. These clothes are in a constant circulation. One will do a period in it and then pass them on so this has been happening quite regularly.

A look from From Somewhere X SPEEDO

But don’t you have to have fairly nice clothes to begin with? I mean nowadays clothes aren’t made for that kind of longevity.

I have to disagree with that because I feel this is a mindset that in a way has also been given to us by the cheap fashion brand and the cheap luxury for a very deliberate reason. They don’t want us to mend our clothes. They want us to buy more. So it’s like they whisper to us “Look, I don’t mind that it’s cheaply made. You don’t mind either, do you?” And then you’re not going to mend it because you have decided it’s cheaply made…but it’s not! It’s simply made.

And the materials are very robust and last a long time because in the majority of the cases of fast fashion and mass-produced luxury they use synthetic materials. Synthetic materials were designed to last 800 years.

Of course, they lose properties because they’re not supreme quality, but if we cultivate a culture that respects those clothes (because simply made or not they’re made by people) and understand that the materials they are made from need to be preserved for a long time in our wardrobes because they are dangerous for the planet, then we would be mending them. And it is those cheap fashion brands that aren’t paying the labor cost and aren’t paying the price to the environment –it is precisely them who should put affordable repairing stations in their stores. Because if you want to sell us so so much then yours is the responsibility to keep it in circulation.

So you keep and mend fast fashion as well?

Yes, I have fast fashion pieces I have kept for 20 years. We need to be careful not to say we shouldn’t mend fast fashion. We should say precisely because it’s cheap and it’s really simply made, I can endeavor to mend it myself. I mean if you have a beautiful 1940s evening gown, I wouldn’t suggest you try and mend it yourself. You’d have to take it to someone capable. But if you got a really simple skirt and all it has is a hem and that hem comes down, bloody hem it yourself or find someone who can.

I guess it goes back to understanding the fabrics and paying attention to how things are made.

Textile innovation and design has been preoccupied with longevity since inception. The minute we learned how to weave, we learned how to darn. And the creation of synthetic fibers is entirely for longevity, for durability, for easiness – easy care, easy wash. So, we need to understand the properties of the fibers just as much as we understand the ingredients of the food. You know if you make a cake, you’d put it in the fridge but you wouldn’t put biscuits in the fridge. So, we need to have that all-encompassing knowledge that analyzes exactly what are clothes are made of in order to be able to care for them adequately.

I personally have been freaking out about synthetic fabrics lately. I’ve recently purchased Guppyfriend bags for myself and our entire small staff at No Kill Mag so we can avoid getting microfibers into the water supply. But I felt like I didn’t know what to do with the synthetics I currently own.

Synthetics? You keep them. They’re wonderful fabrics! When I was a designer, I used to go looking for vintage nylons like they were gold dust because nylon holds colors so well – so these vibrant shades – and I know they were incredibly toxic, of course, but as a designer I would use them on places where they wouldn’t need to be washed so where I could instruct my customer to just sponge clean. I mean if you using an incredibly vibrant nylon as a coat lining for example and it’s warm, it’s amazing, and it’s on the inside of a coat so you don’t really wash it that much! You can look for more sustainable dry cleaning, or really spot wash so again it’s really important that we understand the materials are clothes are made of in order to care for them. If you’re buying polyester make it an overcoat, not a pair of pants, so you don’t have to wash it so often. Why why why buy outerwear like yoga pants out of material linked with deforestation like viscose when wool from responsible sources exist?…there are so many ways of thinking –the book will tell you all of them!

A look from From Somewhere

I know you’re a pioneer of upcycling fabric, did you ever think it would be what it is today?

Yes, I did, but unfortunately, I got my timing slightly wrong. Because I started 20 years ago and I thought it was going to happen within five! In that sense my pioneering was very destructive for me– I wasn’t a traditional designer but I was a very good transformer, and I had a brilliant label and we had an amazing team. But I’m seeing my brand is more relevant now than ever and people know it. People find it or discover it. I can definitely see how pioneering we were which is why mentoring other upcyclists is just so satisfactory because a lifetime of work is finally useful.

When I closed the brand, I was relieved not to be selling clothes anymore. (The commercial aspect really wasn’t me.) But I thought that I was going to lose it forever. I thought that I was going to be kind of missing it.

So, to be able to share the technique, the method, the knowledge with others and leave to them all the stuff about the right buyers and all that, is really a massive privilege. It’s incredible because there was a period in which everything I had done in terms of upcycling probably wasn’t that relevant. And now I am seeing it exploding and now I realize it was relevant and that I can give back all of the things that I learned in what was a really really long and experimental career.

Yes when I was growing up I had to go to Catholic school and I fought my mother on this every year and she finally gave in for ONE year, my junior year in high school when I was 16. And I remember planning out my outfits for the first 30 days of school and almost all my clothes at the time were secondhand and many of my outfits were things I upcycled.

We cannot deny that we’ve got it in our genes. The fact is that whether you like it or not. (and I completely get why sewing went down the drain with burning our bras that women were like “why me, why this, why sewing”… I totally get it) But we’ve got it in our genetics. I was the same. I used to butcher my clothes after school, I used to fiddle with my crochet needle to alter them, it just came instinctively. It’s a bug that doesn’t bite everyone but if it does bite you than you’re done. You’re hooked.

And it’s the same with the designers. Some designers really don’t have it in their signatures but others just think that way. And I’ve come to realize we are a cohort of people who think that way. And you connect with them because it is a different mindset.

We love dressing up, we love new things, how can we change the culture to be consuming less without people feeling like they’re being deprived?

By completely redesigning our high streets and our priorities.

“Right now something like 40 brands control 95% of the market. Tell me that that’s choice? I mean brands – brands call the OVER production of excess volume -they call that choice. I call that an imposition. Choice is variety. Not millions of the same thing in lots of different shades of color. ”

What we need to do is up the visibility of smaller brands, systems, designers, innovators and creators. Then you will be making their lives a hell of a lot easier because they would be more visible, they would have their audience, and citizens/consumers/customers would understand THESE are the people I want to be a customer of – These are the people I am prepared to spend 3 months of my wages saving rather than go shopping at H&M. These are the brands; these are the systems that I want to integrate into my daily life. in order to love my clothes more.

Until we do that, we will be just force-fed unsustainable fashion because let’s be very very clear: I’m not talking about sustainable designers I’m talking about designers, I’m talking about systems and I’m talking about unsustainable designers and unsustainable systems. The brands that we see now on our high street are selling us unsustainable fashion. I need say no more.

How do we talk to people then about H&M having their “conscious collection”

By informing citizens. This is basically how it works today: people see H&M conscious collection. Roughly half will say “oh brilliant!” and the other half will think “greenwash!” but none of them will actually have the knowledge to quantify their opinion whichever way.

“Then they come to people like me and ask “What do you think about this. Is it sustainable or is it a greenwash?” And I say, “My opinion does not matter. What matters is YOUR opinion.” And I can tell you where to go to study to learn in order to develop that opinion. ”

So, I will tell you “I really admire this thinker or find this article on Fashion Revolution or look at these resources” because ultimately we need to be able to decide for ourselves: do we feel that one percent of clothing done consciously and 99 percent done unconsciously is a drop in the ocean? Do we feel that that level of communication, talking about those materials, using those materials, encouraging those materials could be potentially seen as a starting point? You have to decide.

And that’s precisely what we need to do because until we have a generation of customers and citizens that are informed, we aren’t going to be able to change the industry. Brands work for us –but it’s slightly turned recently so we need to have that level of understanding that we have as for example with food…well we know better with food. But that too needs to go much deeper and it’s providing that knowledge that citizens and consumers will be able to make the right choices for them and those choices will differ hugely from one person to the next.

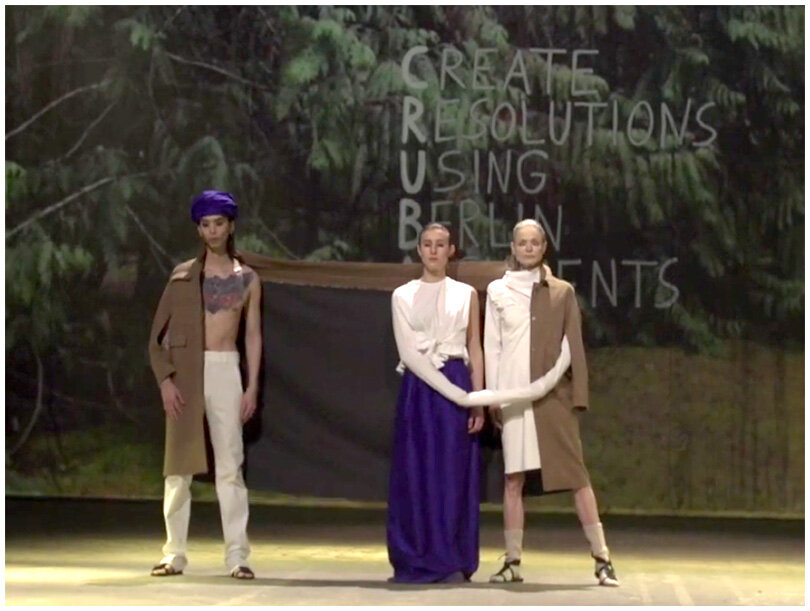

Brand CRUBA featured on Fashion Open Studio

What are things in fashion right now that excite you?

I’m super excited about this initiative called Fashion Open Studio through Fashion Revolution which I am adoring. it is really amazing promoting and supporting young emerging designers and ecosystems. Systems from all over the world, and online has helped us in this case. We have demonstrations and talks and it’s all aimed at transparency, it’s all aimed at really giving unheard voices and unknown designers a platform and a new audience.

I have to say everything that excites me is related to that. To these young designers, to my role as their mentor. That’s the area in my work where I’m the most 100% comfortable and take a massive pleasure and satisfaction in terms of excitement. And I am a believer that finally we will see waste as a resource. And that of course opens up lots of creative opportunities and I’m very excited at seeing some of that happening and also repairing. There’s a brilliant company in London called The Seam that connects customers to seamstresses. All of these kinds of services that are beginning to spring up that excites me as well.

“I collect vintage brooches, badges and pins, which I use to cover moth holes. It all started when one of my favourite jacket’s ‘lapels got attacked, and I covered the holes with every pin I had at my disposal. The final look was totally punk, and the jacket is one of my most admired pieces; I have been photographed wearing it several times. Everybody comments on the pins and brooches, unaware of the secret they are there to hide.” –excerpt from Loved Clothes Last. Photo by Tamzin Haughton

(Back to the book) What will readers learn?

They’ll learn an awful lot about the way that I think because in many ways it’s quite a personal book. It’s between a manual and a manifesto but it’s very much written from my perspective and my point of view and my experience so it’s not an ‘expert’ book -it’s a researched book but I’m not a scholar, I am, in many ways, I’m a thinker. I think things and then I put them into action.

Half the things you will learn relate to your direct relationship to your clothes that you already own: seeing your wardrobe as being a very definite part of the fashion supply chain and your role and responsibility in that latter part of clothing consumption. From end of use to end of life. So really making you aware of all the things that you can do. But it connects you to the supply chain you don’t know. And that’s garment workers, supply chain workers. the toxic impact, the need for transparency – because without that knowledge you’re not going to validate why you’re going to make those changes.

“It is only when you truly understand exactly what went wrong that you can say “well then this is the little bit that I can do to put it right” because we don’t want to go on a diet here. we want people to start a process of change that will last their lifetime. That will become an alternative habit to the habit of mass consuming.”

If I were doing your book launch (I am always thinking like this) I would have it in a gallery with fashion photos that show amazing pieces that have been transformed through mending. To make keeping and fixing your clothes something cool and aspirational.

Exactly! We need to make mending aspirational and available. We can’t make mending only for the rich and those who have the time to do it. We also at the same time need to put mending in every single supermarket and every single H&M of the high street. You know that has to be really cheap. It takes about 3 minutes to hem a simple skirt and yet for a housewife with lots of kids if you spend 2 pounds to hem your skirt that would go a long way to make your life easier and consume less. So we need to have the super beautiful the super aspirational and the 100% fucking democratic.

Learn More:

Fashion Revolution Website | Instagram | Loved Clothes Last

*The 2013 Dhaka garment factory collapse was a structural failure that occurred on 24 April 2013 in the Savar Upazila of Dhaka District, Bangladesh, where an eight-story commercial building called Rana Plaza collapsed. The search for the dead ended on 13 May 2013 with a death toll of 1,134. The factory made clothes for over 29 well known and popular fashion brands across the world and yet none of these brands felt any responsibility for this event as the work was “out sourced” despite the fact that the women who died were doing the work of those brands. This was a wakeup call for those who cared about fashion to see the human rights issues particularly endemic in fast fashion.

-Katya Moorman