This June marks the 80th anniversary of the Zoot Suit Riots, a series of week long race riots that swept Los Angeles in the summer of 1943. The spirit lives on today.

Dressed in a white shirt and pegtop trousers, the fashion of the time for young males influenced by jazz culture, José Díaz headed to a friend’s birthday party in rural Los Angeles. It was the summer of 1942, and 22-year-old Diaz, who was born in Mexico but raised in the United States, was scheduled to report for induction into the U.S. Army the next day. According to accounts, Díaz was excited about the U.S. entering World War II and looked forward to the opportunity to serve his country. Because he would be leaving home for boot camp, he decided at the last minute to attend the party, although he’d initially told his mother he didn’t feel up to going. Toward the end of the night, a group of young people known for trouble showed up seeking revenge for an earlier altercation. A fight broke out, and many were injured. Díaz was left beaten and stabbed, and would later die in the hospital from a brain contusion.

Much like today, fear of the other had firmly permeated the American psyche.

The incident, which became known as The Sleepy Lagoon Murder, sparked widespread fears among white Angelenos over “dangerous, unruly,” Mexican teens, mostly known as zoot suiters for their attire—ballooned pants and long coats. Then-Governor Cuthbert L. Olson used Díaz’s death as a call to action. The Los Angeles police arrested more than 600 Mexican American youth. More than 20 indictments were issued in Díaz’s death, and, in 1943, members of a group called the 38th Street Boys were convicted. One was sentenced to life in prison.

Within months, what became known as the Zoot Suit Riots would erupt

In the throes of WWII, extreme patriotism reigned. Much like today, fear of the other had permeated the American psyche, and many working class whites were emboldened by a pervasive jingoism as the United States asserted its strength on the national stage, while disempowering its own citizens at home.

Japanese Americans were expelled into internment camps, Blacks migrated North in droves to escape racial hostility in the South, and The Bracero Program, the largest U.S. contract labor program, brought several thousand Mexican guest workers into Los Angeles. The “City of Angels” had a booming economy, but discriminatory policies in employment and housing kept people of color on the periphery.

Though about 350,000 Mexican Americans fought in WWII, (More than 500,000 Latinos—including 350,000 Mexican Americans and 53,000 Puerto Ricans served.), their very presence in urban areas was considered a threat.

It was Mexican youth who adopted the attire as an unofficial uniform of resistance.

Riots erupted in various cities across the nation, and the racial tension brewing in Los Angeles placed the Mexican American struggle front and center.

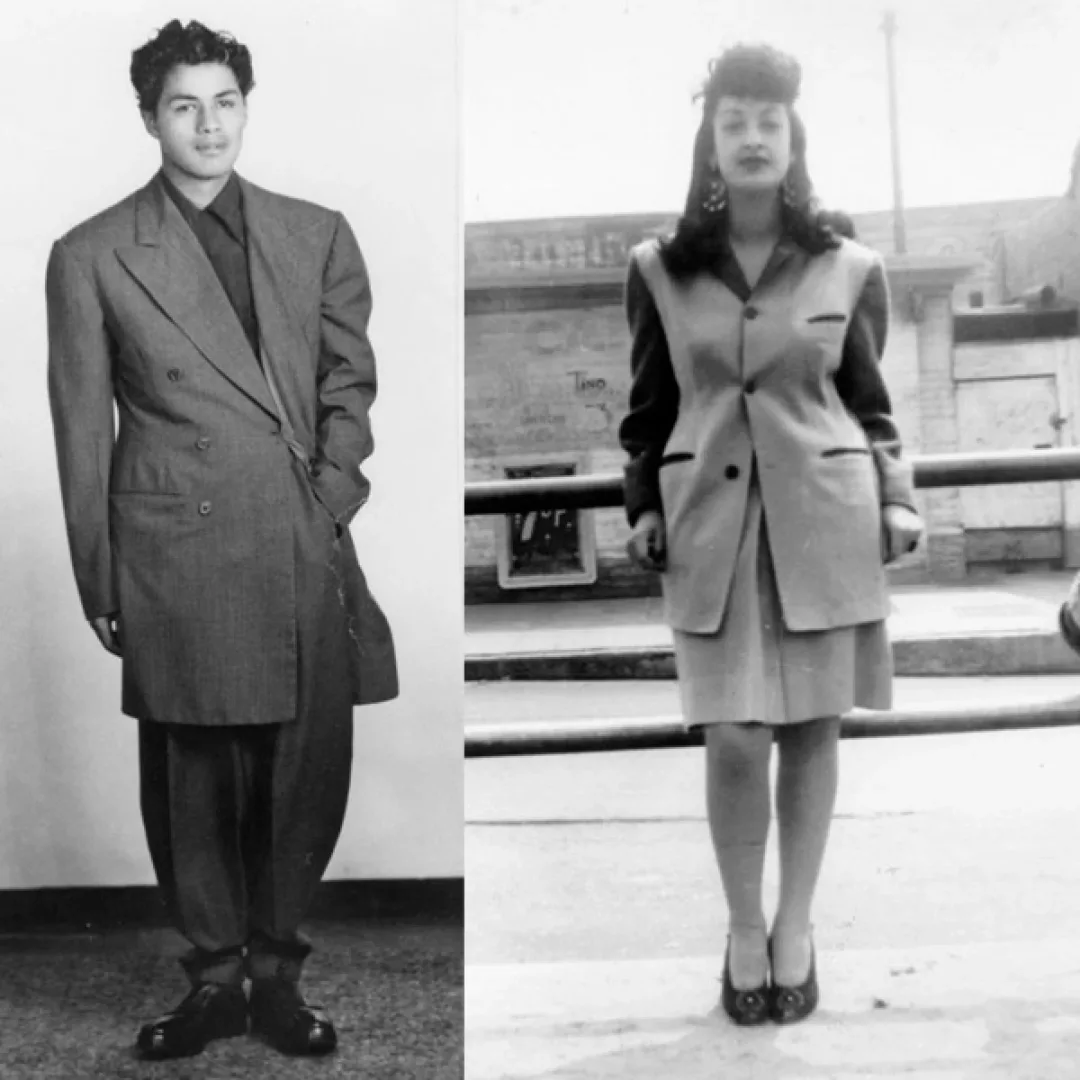

For first- and second-generation Mexican Angelenos, a sense of identity was necessary for survival. As they struggled to navigate older familial and generational values and widespread bigotry, fashion became an important form of cultural expression. For Mexican youth, who would call themselves Pachucos and Pachucas, the zoot suit did just that.

The flamboyant garb, inspired by the drape suits initially popularized by African American jazz musicians such as Cab Calloway, made its first appearances throughout nightclubs in Harlem and New Orleans. The long jackets with exaggerated padded shoulders, high-waisted ballooned trousers, and pork pie hats defined the look and also made it easy to jump, jive, and swing to the fast-paced jazz rhythms. Women wore their own versions too, subverting the status quo and testing established notions of womanhood and femininity. Working class whites, Blacks, and other youth of color, including future activists Malcolm X and Cesar Chavez, embraced the look in its early days. But Mexican youth adopted the attire as an unofficial uniform of resistance—much like young Black boys today who are profiled, criminalized, and murdered in their hoodies for embracing urban fashion and choosing not to conform.

In a national effort to preserve resources, the War Preparedness Board banned the production of wool, pleats, cuffs, and long jackets—key elements that helped define zoot-suiter style. The 1942 mandate had practical purposes, and to resist was dangerous. Bootleg tailors continued sales, and those who stood in defiance were branded unpatriotic when American patriotism was at an all-time high.

There was nothing explicitly Mexican about zoot suits, but boldly demanding to be seen was an affront to American identity.

But Pachucos and Pachucas were American, and in the innovative ways marginalized ethnic groups have always done, they explored ways to carve out an identity in a society that wanted them to disappear. In turn, Mexican youth—as well as Black and Filipino zoot suiters—were hunted, brutally beaten, and stripped of their suits. They then watched servicemen burn their clothes in the streets. Mobs of hundreds of white sailors and Marines poured into Mexican neighborhoods and local hangouts and brutalized them with impunity.

The same bigotry plagues the country today, evidenced by the Latinos, Muslims, Blacks, and Asians subjected to vicious hate crimes for the color of their skin or for wearing “ethnic” clothing. Young zoot suiters learned the very act of daring to assert themselves was, in the minds of many, un-American. Nothing about the zoot suits was explicitly Mexican, but boldly demanding to be seen was an affront to American identity.

As the riots made national news and anti-Mexican sentiment persisted, First Lady Eleanor Roosevelt expressed concern in her column, My Day:

“The question goes deeper than just [zoot] suits. It is a racial protest. I have been worried for a long time about the Mexican racial situation. It is a problem with roots going a long way back, and we do not always face these problems as we should.”

The weeklong race riots ceased when servicemen were confined to their bases and more than 500 Mexican youth were arrested. Smaller clashes continued shortly thereafter, and the L.A. City Council made wearing a zoot suit on Los Angeles streets punishable by a 30-day jail sentence. The riots were arguably the first fashion movement to cause mass civil unrest in American history.

Still, the zoot suit had lasting influence and the riots were a pivotal moment in Mexican American history. Zoot suiters became leaders in the formation of the Chicano Movement during the Civil Rights Era; fought barriers to education, fair pay, and housing; coordinated walkouts and strikes; and formed countless organizations addressing everything from the plight of farmworkers to student activism on college campuses. What’s more, they exposed a struggle that was uniquely Mexican, and helped to affirm Chicanos as a legitimate political force.

Zoot suiters demanded to be seen, and their suits embodied more than style.

The zoot suit spirit inspires urban Mexican style into the 21st century. Today, as inner-city youth continue to endure systemic racism, poverty, incarceration, police brutality, and gang violence, they still use fashion to reclaim their identity. The policing of Black and brown people who dare to challenge the status quo and embrace their own culture, often without a political agenda, continues to this day. Bans on Black hairstyles in the workplace, schools, and the military in recent years (twists were only approved in 2014, locs just this year), or attacks on hijab-wearing women, are modern examples of the ways in which cultural expression is continually silenced. But the pushback from white dominant culture has undeniably been the catalyst for politicizing cultural identity at various points throughout history.

After all, zoot suiters demanded to be seen, and their suits embodied more than style. They became a bold political statement in the face of bigotry, cultural oppression, and injustice.

Youth of color have always been at the forefront of history’s key social movements: subverting cultural norms and giving the middle finger to white supremacy, police brutality, and gendered and racial violence by using fashion and self-expression as a means of not only coping with oppression and subjugation, but also of claiming space rightfully owed and deserved.

–Angela O’Shaughnessy

Related Articles