One of the seriously cool things that happen when entire months center on one “topic” is the potential to discover the unsung, the unknown, and the unheard of. This year, we’ve done a little digging for Women’s History Month and uncovered a few beyond the usual suspects. So don’t be shy! Read, watch, listen –and learn! And, like us, be inspired.

This Bridge Called My Back – Writings by Radical Women of Color

At this point, intersectionality continues to expose interconnected strands of oppression across gender, class, race, and sexuality. This late 20th century ideology created a seismic boom of second-wave feminism. This Bridge Called My Back, from 1981, traces the pathways of women of color and their multifaceted identities, unpacking and informing the masses about the marginalized experience. While writer Norma Alarcón pens a letter to feminism and Chicano culture, artist Betye Saar explores Black caricatures and systemic racism. Between essays, poems, manifestoes, and works of art, each creative uses their tool to eradicate oppressive powers at play and initiate the fight for equality.

Reissued forty years after publication, the anniversary edition contains a new preface by editor Cherríe Moraga reflecting on Bridge‘s “living legacy” and the broader community of women of color activists, writers, and artists whose enduring contributions dovetail with its radical vision.

The Janes

In the pre-Roe v Wade era, there was JANE – not a single individual but an underground network of women providing safe, affordable, and illegal abortions initially unbeknownst to the naked eye. This organization, originating on the South Side of Chicago, emerged during a decade of civil and social unrest, with the collective risking their professional and personal lives for women’s liberation. Coming together from the Civil Rights, Women’s Rights, and Anti-War movements, this eye-opening documentary provides first-hand accounts of the “unlikely outlaws” on the lines and their memories of safe houses, code names, arrests, and determined efforts that saved thousands of lives.

Lady Justice: Women, the Law, and the Battle to Save America

When the 2016 election results broke, legal commentator Dahlia Lithwick was at the front lines and wasn’t alone. Offsetting the turbulent four years of a conservative presidency, Lithwick honors the women who worked tirelessly against ongoing racism, sexism, and xenophobia in the White House and across the country. The pages celebrate attorney general Sally Yates, who used her allyship to discredit the Muslim travel ban. There’s Roberta Kaplan, the famed commercial litigator who stood against antisemitism in Charlottesville. And the spotlight shines on Stacy Abrams, whose efforts protected the voting rights of millions of Georgians and who continues to defend her state. Through a handful of stories and accounts, Lithwick remembers it all, making a point to commemorate heroes in this dark story.

Most exciting, though, is the opening chapter, where Lithwick sets the tone of lady lawyers battling against the very institution they serve. If RBG is the one everyone reveres, we must look beyond her to Pauli Murray. Arrested 15 years before Rosa Parks for refusing to sit in the back of the bus, co-founder of NOW, principal designer of the radical legal theories used to litigate Brown v. the Board of Education, this queer, totally ahead of her time gender non-conforming legal powerhouse remains almost unknown. Is it because, as the great grand-daughter of enslaved people on one side and their owners on the other, she was “one of nature’s experiments– a girl who should have been a boy?” I’m not sure, but I know you’ll want to read this chapter.

The book comes around full circle, offering hope, walking hand in hand with existing change makers and the new wave of activists protecting everyday rights.

Strict Scrutiny

You can’t get enough of Lithwick’s dynamic nature if you’re like us. Listen to her riveting conversations on Strict Scrutiny after reading Lady Justice. The podcast, providing an in-depth analysis of Supreme Court cases and culture, offers the perfect platform to further explore the best-selling book with hosts and law professors Leah Litman, Kate Shaw, and Melissa Murray. As the episodes feature women shaping the legal system, they also investigate complicity in judicial culture, the overturning of our civil rights –abortion being the most glaring example to date. They discuss what it means to rebuild a broken system.

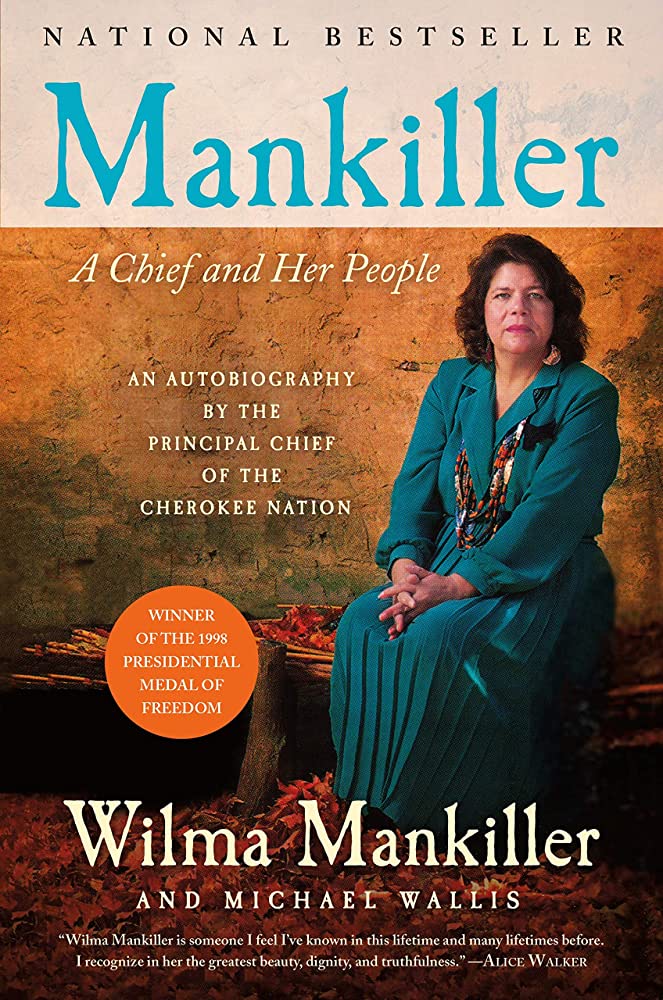

Mankiller: A Chief and Her People

As a Native American activist and community developer, Wilma Mankiller details, in a moving autobiography, her upbringing in the Cherokee tribe and the desire to find identity in an oppressive, Western environment. Serving as the first Principal Chief of the Cherokee nation, she forges activist sensibility, investing her time and efforts in civil rights, women’s liberation, social welfare, housing, and healthcare. Every step of the way, her actions worked to reclaim and preserve Cherokee values and the renewal of the once-strong nation. Wilma Mankiller received widespread recognition and acclaim for her work, and the book provides an intimate and quiet reflection on a woman and the fight for her people.

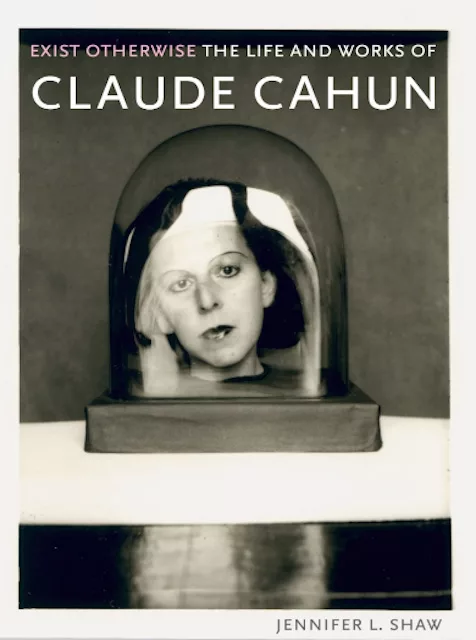

Exist Otherwise: The Life and Works of Claude Cahun

Growing up in France in the early 1920s, Lucy Schwob seemed to be a quiet Jewish girl under the care of her grandmother. So we imagine; got it, Jewish kid in the 20s, we’re in for a heroic tale a la Anne Frank.

Not so fast. As an adult, Lucy became Claude Cahun, a surrealist photographer with a penchant for performative gender. And since there is much truth to the saying that everything old is new again, the utter contemporary, even futuristic take that their work evinces should send you on a deep dive here. Through private black and white photos, the artist reveals herself as a masculine bodybuilder in elaborate makeup, a fairytale character in modest dress, and a mysterious, disembodied face with a shaven head. In the wake of Nazi occupation, the photographer’s darkroom allowed for a veil of secrecy to experiment with gender, sexuality, and ideas of womanhood. The rich text full of Cahun’s photos, montages, and writings tells the tale of a woman unafraid to be herself and the lengths she took for art and identity.

American Revolutionary: The Evolution of Grace Lee Boggs

American Revolutionary follows activist and critical thinker Grace Lee Boggs, spanning her life, legacy, and significant historical events. Having experienced racism first-hand as a Chinese woman, Boggs knew of the unfair treatment faced by her community. But it wasn’t until a walk in her Chicago neighborhood that she saw how interrelated injustices are. She notes, “…I was coming into contact with it as a human thing”. From that point forward, Boggs, who moved to Detroit, stepped into radicalism. She advocated for the Asian American community and the Black Panther Party, feminist circles, environmentalists, and labor rights movements. The film offers a complex p.o.v. into her long life overthrowing unjust systems for universal peace and societal change. Angela Davis, Bill Moyers, Bill Ayers, Ruby Dee and Ossie Davis, Danny Glover, Boggs’s late husband James, and a host of Detroit comrades across three generations help shape this uniquely American story.

Major!

Present at the Stonewall Riots, Miss Major Griffin Tracy’s knowledge about the plights of the LGBTQ+ community is close to her heart. Before her activism, Major experienced her adolescence in queer communities. She attended drag balls and celebrated the world behind gender expression. Her experiences of incarceration, homelessness, and discrimination encouraged her to take action. She became part of grassroots movements nationwide to support other trans women in need. At 82 she is the executive director of her own organization, the Transgender Gender Variant Intersex Justice Project. There she mentors trans youth and continues advocating for all people.

The Heumann Perspective

The highly celebrated internationally recognized mother of disability rights and “a badass”, the incomparable Judy Heumann recently passed away. For anyone who cares about disability rights, she was and remains one of the most relentless agitators for change. Wheelchair-bound after a bout of polio, suffering lack of proper education access because she was, as a five-year-old, considered a “fire hazard”, Heumann came by her radicalism from the inside out.

In 1971 Heumann, denied her teaching license due to her disability, took on the system. In the monumental case of Heumann v. Board of Education of the City of New York, the educator became the first wheelchair user to teach within the city. Heumann spent her years protesting, founding various organizations, and establishing legislative acts to defend and support the disabled. Her biweekly podcast moves between contemporary concerns around disability culture, art, and entertainment and her accomplished past. All episodes of her podcast are available now.

Book of Ages: The Life and Opinions of Jane Franklin

A book by Jill Lepore – of course, that’s always one for the library shelves. But when it’s about Benjamin Franklin’s kid sister Jane Mecom, this promises a radical lens into the 18 century. Writing at a time when women received no formal education and, unlike her wealthy and distinguished brother, poor as a country churchmouse, this Franklin had wit and political acumen to rival her famous sibling. A period of forgotten history comes into view through writings, letters, and objects. The mother of twelve, she performed women’s work (soap making and sewing) to support her family during turbulent times fully. But what stands out most here is that Jane Franklin Mecom was the person Benjamin Franklin corresponded with more than anyone else.

In a review in the New York Times in 2013 Mary Beth Norton wrote:

Lepore shows how the lives of the siblings were irrevocably shaped by gender. The brother, a man able to rise from poverty and to become a successful politician, is universally acknowledged to have been a genius. Was his sister one too? We cannot know, because her life was as much determined by her gender identity as was his: a woman who married young and badly, she spent most of her life mired in poverty, until — having buried her husband and raised children, grandchildren and even great-grandchildren — she was able in her old age to live sparely but comfortably in a brick house in Boston’s North End, to read books her brother supplied and to write him letters. But, Lepore tellingly observes, if she read his memoirs, published before she died in 1794, “she would have discovered: he never mentioned her.”

Related Articles