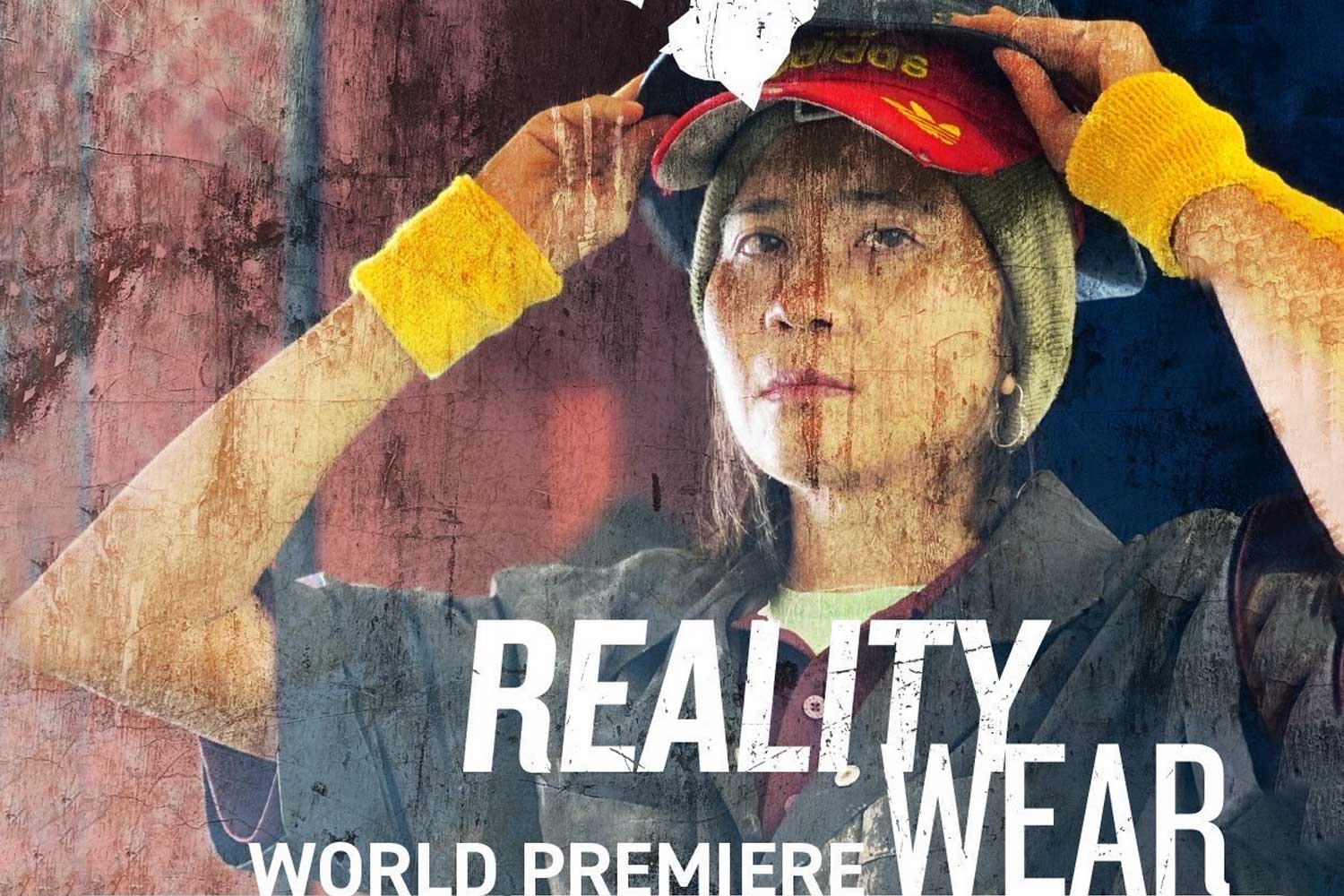

adidas REALITYWEAR to spotlight worker suffering Designed by Pharrell Williams, Bad Bunny, and Philllllthy

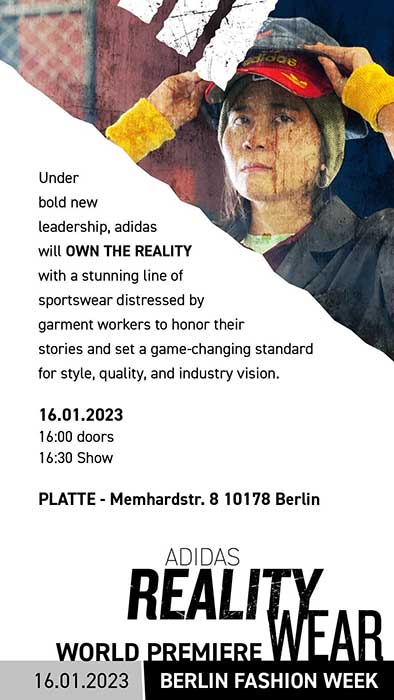

adidas’ bold new plans to “Own the Reality” by cleaning up its supply chain launches at Berlin Fashion week on January 16 with a collection of suffering-forward designs that highlight adidas’ renewed commitment to workers’ rights. The audacious collection of REALITYWEAR includes lust-have contributions from Bad Bunny, Pharrell Williams, and Phillip Leyesa, best known for the upcycling styles of Philllllthy.

“The first step to fixing injustice is admitting the truth and making it visible,” said newly appointed Co-CEO Vay Ya Nak Phoan, the former Cambodian factory worker turned whistleblower who has been appointed alongside CEO Bjørn Gulden to ensure ethical compliance in manufacturing. “By literally wearing the toil of workers on our sleeves, we make it impossible to ignore.“

So began the press release to announce some major changes at the famed German streetwear brand.

The first being the announcement of the new female former factory work now co-CEO Vay Ya Nak Phoan. And the second being that adidas was not only admitting to wage theft but was correcting it and putting on a fashion show during Berlin Fashion Week that interwove these issues into the collection.

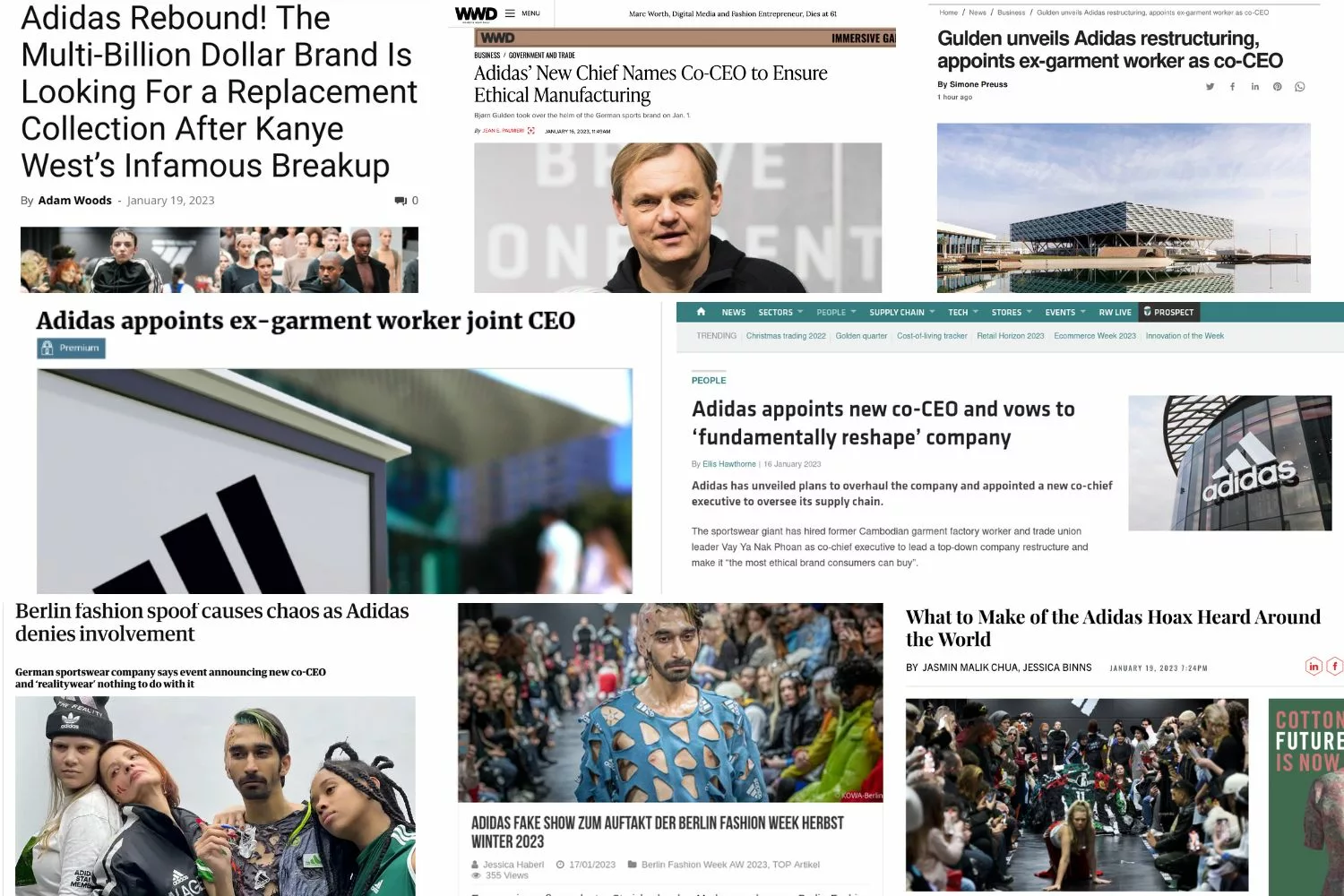

This was sent out to the fashion media who immediately shared it on their websites and social feeds…only it wasn’t real. It was an activist action conducted as a collaboration of several people/groups including The Yes Men, NGO the Clean Clothes Campaign and the design duo Threads and Tits.

The action encompassed an entire fashion week production:

- Sending out the press release

- Creating a collection

- Advertising it around Berlin on posters ahead of the event

- Selling tickets

- Having a show

What made it so unique was that it didn’t just call out adidas but it re-imagined how adidas could actually shift their position to make real world positive change. Demonstrating to the “impossible is nothing” brand just how possible fairness and equity in their supply chain can be.

We spoke with Ilana Winterstein from the Clean Clothes Campaign to find out more.

No Kill Mag: What is the Clean Clothes Campaign?

Ilana: It’s a global network of over 235 organizations in over 45 countries. We connect activists in garment-producing and consumer countries, and our members include NGOs, grassroots unions in garment-producing countries, trade unions, activists, feminist organizations, and CSOs. The role of the network is to amplify the voices and demands of garment workers and to push for systemic change and an end to exploitation in the global garment industry. I work on campaigns, and I coordinate urgent appeal cases.

Give us an example

If something happens to a group of workers, such as wage theft, or they get fired for joining a union, they can approach the Clean Clothes Campaign for support in their fight for their rights. A case group is then formed, the campaign strategy evolves from there, and we fight for workers to get justice.

I first learned about the exploitation of workers after the collapse at Rana Plaza. Is this when the Clean Clothes Campaign started?

It started in 1989. Rana Plaza, which is coming to its 10th anniversary, was the biggest disaster in the industry, but the issues are long-standing. And all of the problems that led to Rana Plaza have been happening elsewhere on a smaller scale:

- The poverty wages, which meant workers didn’t have a choice but to enter the visibly unsafe factory for fear of having their wages docked.

- The lack of union rights which meant they couldn’t collectively fight for their rights.

- The criminally dangerous factories.

- The high quotas.

- The social audits that act to protect brand reputation rather than workers’ rights.

Exploitation is the backbone of the current garment industry model. And the Rana Plaza collapse essentially shone a powerful spotlight on what was already happening.

And Covid made it worse?

The pandemic really exposed the injustice and inequality in the industry. Since the onset of Covid, we’ve seen a steep rise in wage and severance theft cases and violations against union rights under the guise of necessary pandemic responses. For example, factories will say they need to downsize their workforce due to reduced orders, but the union members get fired. The Pay Your Workers campaign began in the early days of the pandemic when we suddenly saw brands pulling orders, not paying for orders already in production, or demanding a price reduction. The industry structure means that brands hold all the power and profits and essentially control everything. They act with impunity, and the pressure is pushed down the chain. So, when they don’t pay for orders, the impact is that workers don’t get paid and struggle to survive.

All of the risks fall to them. Millions of workers were left without the money they needed to survive or the wages they had earned. And yet brands continued to turn profits.

It’s horrific.

Brands would say, “oh, it’s a hard time for everyone,” but the CEOs aren’t foraging for food on the roadside!

More like “Life’s hard. I can’t have my 3rd vacation home!”

Exactly. And in terms of the Pay Your Workers campaign, we’re targeting adidas because of their hypocrisy in how they portray themselves. They like to be seen as an industry leader and very ethical.

They use women’s empowerment to sell and market their clothes. And they’re very good at it. But where is the empowerment for their female workforce who make their clothes and profits possible? We wanted to shine a spotlight there and say, Put some action behind these words!

We have so much we want to talk to you about, but to respect your time, let’s talk about this action –which was later called a hoax. I think “hoax” is too dismissive because it was an activist action. How did it start out? How did you even come up with that idea?

Because it’s brilliant and we want people to do it everywhere.

We worked with the Yes Men, who are professional prankster activists. We have been working with them for some time on how to draw public attention to this issue. To really pin adidas down. And when adidas announced a new CEO, we thought, okay, what would be a radical change? We asked ourselves: What could they do? What would be a utopian vision, and what would we want adidas to do if they were the ethical leaders they position themselves as?

Could you share with us the details of the action?

There were two parts. One was the announcement of a revolutionary restructuring of their leadership team with their new co-CEO. This former Cambodian factory worker would oversee ethics and ensure respect for human rights.

And then there’s the “RealityWear” clothing line. Which debuted at Berlin Fashion Week with a sold-out fashion show at a venue opposite adidas’ flagship store.

The collection was deliberately offensive because what we put down the runway was the reality of what happens to workers in adidas’ supply chain. There’s union-busting, poverty wages, rampant abuse and violations. And this collection was adidas supposedly owning all of their shit! And people believed it.

The fashionista audience thought, “Wow, it’s courageous for adidas to own their mistakes,” People told me how much they loved the collection and wanted to buy the pieces. It was fascinating to see the response of the audience. As consumers, we’re so distanced from the lives of garment workers. Even though we know about sweatshop labor and fast fashion.

There’s so much money in the glossy image. The image that brands like adidas want to present to us because that’s what we’re buying into. You could purchase the same sweatpants somewhere else, but you’re buying adidas ones because you want to be part of that image, one that’s based on wokewashing, which adidas is a master of.

Editor’s Note: Interview with the designers Threads + Tits here

Right. I believe that we invent the future through our actions. And this action said, Stop accepting what these brands say without question. Stop accepting “this is how it is.” Instead, “Look, there could be this other possibility.” But adidas’ reaction was to just completely shut down. The brand has these signposts of diversity and inclusion, and equity. But it’s not real it’s “blah blah blah”… (to quote Greta).

Yes, it’s meaningless CSR speak. Well, it’s not meaningless because it sells more clothes. But I would love it if someone within adidas looked at our action and said “you know, people thought we could do this, so let’s do it. What is genuinely stopping us?”

Because nothing is stopping them. They could radically change their operations and center workers’ voices and rights. And that’s how the industry should work. But it’s so skewed now, and the power imbalance is so vast. It would be fantastic for a company as big as adidas to take such a bold step to prioritize workers’ rights.

Right. And take responsibility. Their new CEO is a white man, and its garment workers are overwhelmingly women. And I think in my experience, those at the forefront of workers’ rights and climate change are women…

Yes, if we look at the history of where we are today as a global society, white men have had a lot of chances to lead and to change things. And the global garment industry echoes colonialism – the profits go to those at the top. Generally white men, and yet the labor is done in production countries mainly by women of color. And we’re not seeing the progress that’s needed in the industry. Give power to other voices – make room for other people to lead.

How long did it take to put together this campaign?

We worked on it with the Yes Men for a few months because it was very detailed. We released a series of hoax press releases, a fake adidas website, and a promo video introducing the new co-CEO. While also working with Thread and Tits, the German design duo who made the “RealityWear” collection. So there were a lot of parts, and the Yes Men were excellent at coordinating and ensuring that it all came together in Berlin.

And outside the venue, which was very close to the adidas flagship store in Berlin, there were billboards with our posters and other details that you wouldn’t have seen in the media but that were in Berlin. People were confronted with all of this imagery around the new RealityWear collection, which hopefully would lead people to wonder what was happening and look into it further.

So a lot of press bought into it?

Yes, we had a lot of global coverage! Numerous sites bought into the first press release and believed it was real, including Australia’s leading business outlet, and then the coverage once the hoax broke went even wider. The Guardian and Der Spiegel broke the story, and it snowballed from there.

And adidas refused to comment on any of it?

Yes, adidas initially refused to comment, and eventually, they were pushed into giving a statement that they respect workers’ rights. But again, where is the action behind their words? Where are they investing in workers’ rights? How are they ensuring an end to union busting in their supply chain and stopping wage theft?

It’s also important to stress that the Pay Your Workers campaign is not solely about adidas. They are one of our targets. But the aim is for all brands to sign this legally binding agreement. Currently, brands sign up for voluntary initiatives and codes of conduct that they draw up. The industry structure is designed to protect brands, and when violations occur, nothing legally holds them accountable. That’s where the Pay Your Workers campaign steps in. We want all brands to sign this binding agreement on wages, severance and freedom of association.

Sometimes there’s a win. There was a good one with Victoria’s Secret?

Yes! There are wins! Recently more than 1,250 workers who were making Victoria’s Secret lingerie in Thailand won 8.3 million dollars in back pay. It’s the most significant severance theft victory at a single factory in the garment industry. You can read the details online.

Workers shouldn’t be forced to campaign and fight for money legally owed to them.

One case I’ve been working on for 8 years is against Uniqlo. They owe 2000 Indonesian garment workers 5.5 million US dollars in severance pay. And that was eight years ago. So if you factored in inflation, it would be a lot more.

EDITOR’s Note: To put this in context, Roger Federer, long considered the “sport’s marketers’ dream, the most gracious gentleman,” signed a 10-year $300 million deal to be a brand ambassador for Uniqlo, one of the few athletes to earn over a billion dollars by “selling the dream.”

Yet Uniqlo, one of the most valuable brands in the world, can turn its back on them and refuse to pay up, and there’s no legal way to hold the brand to account. This is a significant failing in the industry; again, workers suffer.

In many garment-producing countries, the minimum wage is very, very low, and there aren’t adequate social protection systems in place, meaning there aren’t safety nets to catch workers if they lose their jobs. So the government mandates severance, and it is the responsibility of the employer to pay it, yet severance theft is a known and common issue across the industry. And the employer is the factory owner, not the brand, even though they’re making the products and profits for the brands.

And because of that, brands can turn around and say, oh, yeah, we see you’re owed this money, and the factory owner should pay it. But the owner has been squeezed on price because brands use aggressive purchasing practices in a global race to the bottom. They push everything lower and lower, squeezing down the chain, with garment workers shouldering most of the risk. If factories try to demand more from brands, the brands will take their business elsewhere.

Part of the Pay Your Workers agreement includes establishing a severance guarantee fund. Brands would pay into this fund. Then when a factory closes or does a mass layoff of workers, the money is already there. Workers don’t have to go through a long, drawn-out campaign to try and receive the money they’ve already earned.

Right

And, you know, the cases that come to us are the tip of the iceberg. In many cases, workers don’t win the money they’re owed. And it can be life or death money. They have to pull their kids out of school because they can’t afford the textbooks, the uniform, three meals a day, or even medical bills. And yet they work seven days per week for one of the biggest industries on the planet. So the impact is enormous, and it’s cross-generational. Brands need to be held accountable for this.

Does calling things out or creating awareness on social media help at all?

Yes, it does help. It helps when people find out about an issue and go to the brand’s social media and ask them directly, what are you doing about this abuse? Why are you not paying people? Because brands are all about their image, and they’re meticulous about their social media output and how they represent themselves.

And they do not want people on their pages highlighting human rights violations in their supply chain. I think it definitely helps.

As an organization, we don’t promote boycotting because it will directly affect the workers. A brand might pull out of a factory or country, leaving workers without jobs. Our role is to amplify workers’ voices and demands, so unless the workers in a specific factory or country call for a boycott, we won’t do that.

What we want is for brands to make long-term commitments with factories. And that takes dedication, time, and investment from the brands. And it takes a significant change to their purchasing practices to prioritize workers’ rights.

That’s an important point – not to boycott. That makes sense when you say that. And you know, my first instinct would be, don’t shop here.

Yes, and as a consumer, where you spend your money is how you show your values. So I understand that initial impulse. But you have a voice and brands care about the people who give them their money.

So if you take to social media or go into a store and say, “Hey, I’m a customer, and I want to know what you are doing for the women who made these clothes but aren’t being paid. What is adidas doing?” that gets reported up the chain. Then there’s internal pressure and a situation the management doesn’t want to deal with. And they have to talk to their staff about this case or what they’re doing or not doing to resolve it. That kind of pressure really does create change.

Signing petitions is valuable as well. I know it can feel like there are endless petitions, and sometimes you feel like, “What is it really doing? I’m adding my name, but is there any point?”

But from where we stand, there definitely is a point because these petitions show brands that their customers care. And if enough people care, then they will make a change.

That’s great. We also teach in a graduate communication design program where many students feel helpless looking at these issues. And they’re like, “oh, but just doing things online doesn’t matter.”

So we can return to them and say, Yes, it does, it does matter. Yes, you can think of actions to do, and we can get inspired by this one with adidas. Come up with something here in New York! But in the meantime, you can go on this social. You can sign the petitions.

It’s so important. I know how it can feel hopeless, or you wonder what impact you can have. But it does really have an effect. And showing solidarity has a huge impact. If workers are striking, maybe I can’t physically stand with them on a picket line, but I can show my solidarity online and send a message that says, “I support you.” That has an impact on the people striking. They don’t feel so alone. They know that people stand by them.

And in terms of our campaigns –solidarity is an essential part of it. It’s letting garment workers know they’re not alone in this struggle for their human rights. That consumers care and are amplifying their voices and demands.

To wrap it up, I know it’s easy to talk about the bad and the overwhelming, but what’s the positive?

When we win a case, it’s incredible. About two years ago, I worked on a case called the Kanlayanee Case, which involved Tesco, Starbucks, Disney and NBCUniversal, four of the biggest companies in the world. We were working with 26 Burmese migrant workers in Thailand who worked in this tiny sweatshop where they were exploited and suffered abuse. And it was a very creative campaign to work on.

And when we won, it was terrific because the workers had been so involved in the entire campaign. At one point, they dressed up as minions and created a photo series of their daily reality, which included having to forage for weeds from the roadside because they couldn’t afford food. They made their own minion costumes, and the juxtaposition of their situation with the minions made people connect with the case.

And knowing what a huge difference that that money –and again, it’s money that was owed to them– would make to their lives was very motivating, and I really enjoyed working on the case with them. And this is money that the workers earned.

I think that’s one of the most important messages to these brands – it’s not charity when you pay your workers! We’re just asking for the bare minimum at this point. We’re not saying, “Could you do a really lovely thing?” We’re saying, “These people make your clothes. Pay them!”

And at this moment, it’s paying them poverty wages. It’s not even paying them a living wage.

It’s unbelievable that this should even be an issue. It could be solved so quickly because they have so much money.

Yes, but as you mentioned, there’s this impression that “this is the way it is.” Brands claim, “We’re doing our best within this structure. You know, this is how it works.”

The brands are making the rules of this industry. They could change it overnight. They could radically center people and the planet. You know, they could do that, but they haven’t yet.

–Katya Moorman + KL Dunn

About Ilana Winterstein

A background in theater and a strong sense of social justice led Ilana to working on human rights campaigns and activism. She currently works in the International Office of the Clean Clothes Campaign. Their job is to facilitate collaboration on campaigns and to help ensure that communication through the network works well and campaign collaboration is as fluid as it can be.

Related Articles