An Interview with Janelle Abbott aka JRAT

The future needs you now, you need the future

Janelle Abbott, a.k.a JRAT, describes herself more as an artist than a designer. As an all around creative, she is putting her energy into a little bit of everything to deal with the weight of the material of the world. Making wearable furniture, zero waste clothing, art; she is a jack of all sustainable and ethical trades.

I had a Zoom interview with her and got a full rundown of her life–from being raised in the industry, battling some unaccepting professors in college, to her life today in Seattle with her flip phone and “brand” JRAT.

A young Janelle hard at work

Leah/NKM: I would love to hear an introduction about you and how you describe yourself… an artist or a designer?

Janelle: I would describe myself as an artist more than a designer. I grew up in the Pacific Northwest, where my parents owned a clothing manufacturing company called Amanda Gray. You can still find their stuff out there, but the business is no longer in existence.

In the late ‘80s, early ‘90s there was still a decent fashion manufacturing industry based in Seattle, so all the clothing was created here. I was home schooled at the time, so I just hung out at the warehouse. That’s where I learned how to sew –on an industrial machine.

That early exposure to the behind the scenes of fashion production inspired me to go to Parsons (School of Design) where I graduated in 2012. It was at school that I increased my commitment to sustainable fashion.

“I learned about the issue of modern slavery and human trafficking when I was 15. Slavery historically has been a huge issue in the production of clothing— from the Trans-Atlantic slave trade, which was largely fueled by the profitability of growing cotton in the American south, to the rise of fast fashion in the early 2000s. Opaque international production chains trap people in situations of debt bondage and slavery, just for the sake of corporate shareholders and CEOS.”

So at 15, I decided I couldn’t buy newly manufactured clothing—unless I knew for certain that it was made ethically, along every step of supply chain. Growing and processing the fiber, crafting the fabric, cutting and sewing, shipping and retail; garment supply chains are complex, with many different moving parts, but each component must to be held accountable for the way in which they’re treating their employees and the environment.

At Parsons I learned about the zero waste design methodology which addressed another issue in fashion: environmental degradation.

Zero waste pattern drafting is effectively a practice of designing pattern pieces like puzzles–your marker is a perfect square or rectangle, so nothing gets wasted. With traditional methodologies, at least 15% of material gets thrown away during production, and if it’s polyester it’s going to take a millennia to degrade in a landfill.

I’m very rigid about adhering to these particular ethical design codes, among others, and in part that’s why I’ve kept my practice insular; I source the material second hand, I create the patterns if I’m doing flat patterning or I hand drape everything if I’m using different parts of old clothing cobbled together to create my work, and I do all of the production. I very rarely outsource my production, and if I do, it’s someone I know personally and respect and want to support as an artist.

It’s a tough road because it does require a lot of my time and energy and because systems like fast fashion have really devalued the worth of clothing, especially in the point of view of the consumer. It’s really hard to convince people, No! actually this jacket is worth $400 and pretty much every item of clothing available even in a run-of-the-mill retail store should be at least 3-4 times more expensive than it currently is. The use of slave-labor has allowed for large companies to provide clothing at rock bottom prices.

So this has been something, you said you were 15, you were very young when you recognized this and that was a big turning point. When you went to college at Parsons, did you have to push for what you believed in? Were professors and other people telling you, No this isn’t how you do it? Because Parsons has sustainability built into the school’s practices now, but has that changed in the last decade?

I think Parsons has changed significantly since I was there. The only sustainability focused class at the fashion school was the zero waste design class, which I took the first time that it was ever offered by Timo Rissanen –who has left Parsons at this point. He really created the foundation for sustainability in fashion that the school has built upon today.

I definitely had to fight against my professors all throughout my education because many of them came from different sectors of the industry that were very committed to the old ways,

(chuckles) Like one professor in particular was very much like a Ralph Lauren designer, so he would always criticize me for not having a liberty print incorporated in my work.

“I’m hand painting fabric and talking about these very esoteric concepts that were inspiring the things I was designing and he didn’t get me and didn’t even try to understand me! He just wanted to prescribe to me the way he believed designers should behave and participate in the industry and that was really frustrating.”

I felt pressured to put on the uniform and become whoever the industry expects me to be. But instead of succumbing, I just ignored my professors and kept doing what I was doing. I had one professor in a pattern drafting class come around to my dogged commitment to zero waste design and within the context of the work I was trying to do, she gave me advice about how to do that work better, as opposed to how to change my work to be more like the traditional process. She said, “Here are some ideas within the zero waste framework to make your garment fit better and still be zero waste”. I really respected that professor in the end, but it took some squabbles to come to that place of, you’re not going to change me, you just have to show up where I’m at and help me get where I want to go, not where you think I should be.

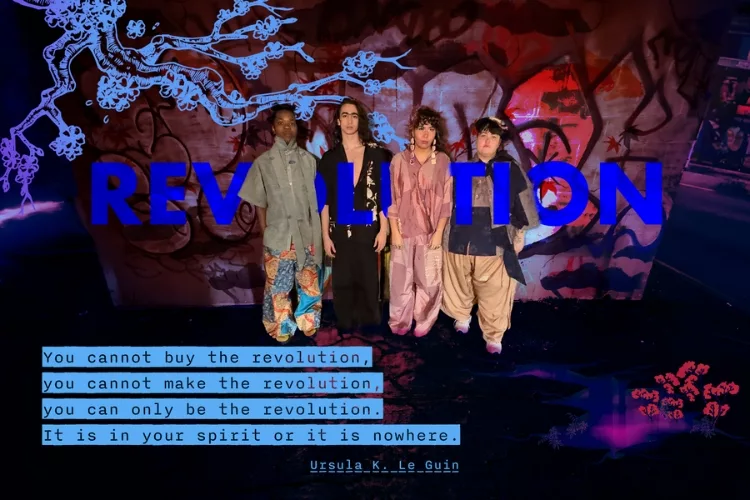

Janelle Abbott in JRAT

Let’s talk JRAT! What was the start of that? Do you want to talk about the brand a bit?

JRAT is many different things… It is my brand, but it’s also my artist name and was previously a fictitious newspaper that I wrote for about 10 years. It was called the JR Abbott Times, so that’s where JRAT comes from. But I also identify as being kind of a street rat… for many years I would ‘freegan’ or dumpster dive for all my food.

When I returned to Seattle after college, I was making garments casually, just small collections once or twice a year, but I wasn’t on Instagram at the time, so I wasn’t promoting and building my brand in the public sphere. I was just selling at a shop here in Seattle and working random but fulfilling jobs. About two years ago I became more serious about making collections more consistently as well as promoting and selling my work.

I am really intentional about how I source my materials. I use second hand clothing found on the street in free boxes or people give to me. If someone messages me saying, I’m cleaning out my closet and I have stuff I can’t donate. Do you want it? I’ll be like send me pictures! and they will send me photos and I’m like Ugh I don’t want any of this! –but I just take it anyways to prevent regrettable pieces from dying slowly in a thrift store or landfill. It can be inspiration for me too, trying to invest the time and energy into transforming something that probably has no other life, you know, like a stupid polyester jacket from Zara that somebody bought for their first corporate job. Nobody wants that, but maybe I do? I have the interest of re-contextualizing things that exist but can no longer be used as is.

Also, my grandma thrifts and often when I visit her she has a bag of fabric and clothes for me. An abundance of materials has been a big motivation to create collections because it needs to move out of my studio!

“I’ve had pretty extreme anxiety since childhood and have found making art to be an effective tool for processing my anxiety.”

Pieces that were remade for client Misty Dawn as part of JRAT’s Wardrobe Therapy

Another aspect of JRAT is a project called Wardrobe Therapy, where I work directly with private clients to transform the clothing they love but seldom wear, into revitalized pieces they can wear once again. The process begins with an in-depth interview about the clients history with clothing –where they’ve been, where they are, and where they want to go. We then select a group garments from their wardrobe and I design pieces to be created from the clothing they already own.

It’s a very intimate process. We do a fitting mid-construction to make sure the garments truly address the fit desires of the client and then the finale is a photoshoot, but that’s become difficult because of Covid. After 2 or 3 years of Wardrobe Therapy, I’ve learned a lot about different peoples understand their world through the lens of clothing. I’ve taken measurements from almost 70 different people at this point and they are all spectrums of shape and size, so I think that’s really helped me in my personal practice to be a little more cognizant of making one-of-a-kind clothing that can fit a variety of different bodies.

A wearable chair by JRAT

Finally, within the world of JRAT, I make art. I’ve been working on wearable furniture lately: a chair that has a jacket built in so when you sit in the chair you can put on the jacket and get stuck in the chair— it’s an extreme relaxation tool or meditation space. I’ve also been making rugs that have pants woven into them, so you can lie down and wear the pants and become a part of the rug and feel really grounded.

JRAT ultimately is not an obviously, straightforward brand that just makes and sells product… I don’t know how to do that and I’m very envious of people who can because it seems way easy to manage! I’m over here doing several different things simultaneously, throwing my energy all over the place, but I think I prefer it that way..

How has Covid impacted how you source materials? Or is what you get from your Grandma and friends sufficient?

I lucked out at the end of 2019. I got connected to a group that was reinventing an old curtain factory in Seattle to become an art space and in the basement there were shelves and shelves of deadstock curtain textiles and so I was able to buy several dozen bolts off them. So at the start of Covid I had that huge stack of flat material, but I have also over the years collected scraps of different clothing and fabrics that I have cataloged by color.

I am trying to work through my backlog of material right now. So I really don’t need anything to come in, but I was out thrifting recently and bought a few things and then scolded myself for it but when you find a zebra print bed sheet, you buy it, because you need that!

(in regards to Wardrobe Therapy and Covid)

In the past I’d done several projects fully remote but with Covid, I have to interview even local clients through Zoom. It’s made scheduling easier, but the design portion of the process is more difficult. I have to rely on clients take their own measurements, which is risky. I’ll get really weird numbers back only to find out they’ve done some in centimeters and some in inches! But in the end, things typically work out.

What is your design process like?

There’s no general prescription, it’s case by case and dependent on material. Sometimes my design process starts as a pile of clothing: I try to look at shapes within the garments that can be re-contextualized, arm holes turn into crotches, sleeves into legs, legs into sleeves.

Sometimes my design process begins with gathering a group of disparate material that have a linear narrative or relationship. I’ll start by making one piece, and that’ll be the spark to build the rest of the collection around. I do give thought to things like styling and marketing—I try to build a variety of pieces like jackets, dresses, pants, skirts, jumpsuits, weird non-garment garments like aprons.

By the end of any collection, my main concern is to ensure that all of the material I began with has been used. If I start with a thrifted garment, I am sure the whole garment gets used within the project somehow; it’s another way to be zero waste.

My process can be aesthetically varied, but I do have some themes that pop up from collection to collection: I use this pleated trim a lot right now, but at the same time looking from one collection to the next, they don’t share the same aesthetic or color palette or even fit. Things can get really out of control and I’m okay with that. The work can very deviate, even from things that I would want to wear and I’m okay with that too. I see a lot of designers who are really good at keeping their aesthetic very narrow and consistent and I think that’s very good for clients because they always know what to expect but that’s just not how I work. I really try to let each project guide itself and become whatever it is it wants to be and just accept that.

Where can the public get your pieces?

On Depop right now, I have some simpler, more affordable pieces. I offer my collections through retailers like Café Forgot, Stand Up Comedy in Portland, Kathleen in Los Angeles , ATIKA London (one of a kind pieces are not online, but you can message them), and Kunst in Montreal.

What’s next for you? Any planned future endeavors or collaborations planned?

I have two things coming up. One of them is a political pamphlet through a gallery and publisher called Mount Analogue based in Seattle and Los Angeles. They have been doing a political pamphlet series for the last 6 months so mine is going to be the last.

It is about slavery and the production of clothing, as well as a guide for consumers –kind of a DIY Wardrobe Therapy to aid people in detaching from the support of slavery in the production of clothing as well as advocate for reforms.

And then I just put up an installation with the city of Seattle as part of their Flow 2020 project. I’ve spent the past few months wrapping wire with old clothes to form the words “The future needs you now, you need the future” along a fence outside a construction site. I personally have felt a lot of existential dread about the future of our planet in light of climate change, as well general depression. Suicide has been on the rise in the past 20 years and only made worse by Covid. I wanted to send the message that if you exist in the world today, we need you in the world tomorrow and there is always hope for collective action and mutual aid, for people to come together to fight for the survival of our planet as well as one another.

In my fashion practice, I am working on Part 2 of a collection I did for ATIKA London last year called No Country For Old Clowns.

And I am always working on new furniture! I have a new wearable rug and wearable chair I am going to do a video series with. I think those are the biggest things on the horizon. I have a lot brewing and I need to figure out what I want to invest my time in next.

Dara Breeze modeling JRAT

JUST LAUNCHED: JRAT X DARA BREEZE

After our interview JRAT announced a cross promo project with Seattle photographer Dara Breeze. Together they are hosting a fundraiser for the Loveland Foundation Therapy Fund which provides scholarships to Black womxn and girls seeking mental health counseling. Offering various ruffle hats and clown collars which Dara photographed, 100% of the proceeds will be donated! More information HERE

Mental health is an absolute necessity, especially when living within all of the broken systems our world is wrought with. Dara took these beautiful images as a practice of self-love and self-care—they also beautiful illustrate the the various ways you can style the Ruffle Clown Collar! Wear it around your neck, head, shoulders, and anywhere else it fits. The Ruffle Hat has long ties which can be styled as a scarf or bow.

Where do you get your inspiration from? Is it fashion or art based?

I have never really followed fashion… I don’t look at NYFW, I don’t go to normal stores, I really only end up in thrift stores. So I try to keep myself detached from whatever is happening in the broader world of design, but I do believe in the collective unconscious and the impossibility of coming up with an original idea, like that we are all recycling concepts over and over again, so I think what ultimately inspires me is happenstance, just coming upon a thing and following wherever it leads. History has been inspirational for me as well, if I do look at fashion it will be to the 1800s and earlier, all the different ways people dressed based on the technological and construction know-how of the time.

I did a collection last year called ode to the USPS because I am a super fan of the postal service and they were also being dismantled during the Trump administration. That was a moment where I had materials that were reminiscent of postal worker uniforms and also big bag of patches that my friend had bought me years ago. So I created that little collection and it was very clear point of inspiration. But with other collections, it’s more abstract and predicated by the materials. There is a lot of art that I appreciate but it’s not an active or direct source of inspiration. Like the work of Ana Mendieta, you can see notes of her work in mine, but it’s more ephemeral than factual.

Where to find Janelle & JRAT: Instagram | DEPOP | Website

–Leah Flannery