Prefer to read in Spanish? Click here!

“By telling stories I realized that García Bello is not me, but rather a voice inside many people sharing the same narrative”

Argentine designer, Juliana Gracia Bello, brings with her deep emotional baggage that appeals to environmental awareness. Born in Tierra del Fuego (the southernmost province in the world), she has always lived surrounded by nature, taking part in environmental causes and having inherited sustainable values from her family.

Currently living in the Netherlands, she won the famous Redress Award 2020 contest with her established brand Garcia Bello. Blending the donations that she received and an impeccable reconstruction method, while employing a zero-waste pattern with a final touch of profound storytelling, she amazed the jury with her collection Herencia.

NKM/Nazarena: Can you describe your experience of creating a collection and participating in a worldwide competition during a lockdown? Was it hard to readapt to the new circumstances?

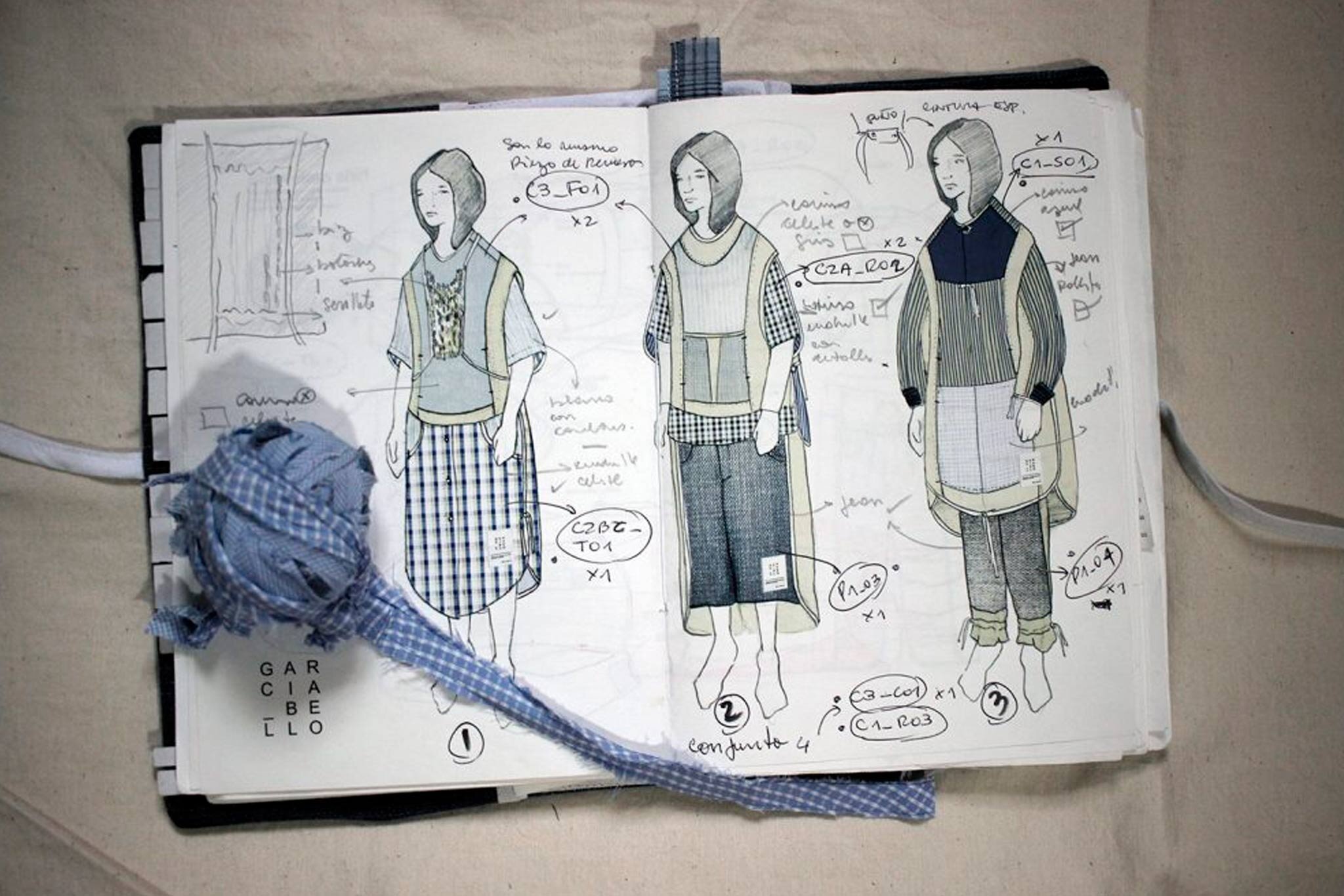

JULIANA: When I enrolled in Redress with the Herencia collection, the COVID outbreak had just started and I was already working on Esencia (2020). The inspiration I received both from this collection and from working with my neighbors made me consider taking part in the competition. I decided to continue working with the neighborhood (something I have been doing for many years) and to apply this to a narrower collection with a smaller system. The particularity of what I presented in Redress is a garment system built from a specific amount of garments that deconstructs each other and creates a closed collection. That collection can be scalable, but initially, 9 garments can generate 15 different ones.

The contest rules said, “You have to generate five sets and it has to be an industrial collection.” so I designed according to those guidelines. I wanted to convey the concept of Herencia. This individual, homemade workshop process that I learned from my family could be adapted to large industries. I think because I thought it was so specific, I must have won. Instead of submitting something I already had, I prepared it for the contest.

We moved here in October 2019, but it was only in March that we had our apartment and workshop. The machine with which I sewed Herencia was donated to me by a neighbor. I had nothing. So I said, “I’m going to take what I learned with my family in Argentina and put it to the test.” and that’s how the collection started. Using what others no longer used, I showed that it is possible to generate a good fashion collection with little, and thus Herencia was born.

HERENCIA: womenswear winner collection from the Redress Design Award 2020

It has been a year since you won the First Prize in the Redress Design Award 2020. How was your transition from the competition to launching your eponymous brand? What was the biggest challenge for you?

For me, the biggest challenge we have as a brand (apart from what I am as a designer) is to be enduring. Too many people depend on García Bello and, expanding the work team and making that team enduring, would be the biggest challenge.

There are months in which we work less because there are fewer projects, that is why we propose better-sustained work and that the people we work with can always receive a salary. It would be even interesting to have people constantly working inside the workshop; it would be something I would like to grow as a brand.

From the contest to here, I started to think of myself as a brand rather than a signature designer (in Argentina, I worked on authorship, more personal issues and more unique garments). A brand includes many other voices, not just mine. Suddenly, the brand and work expanded quite a bit. There are many more people and I also distanced myself a little from the brand.

You said the collection Esencia (Essence, in English) and Herencia (Heritage, in English) are strongly connected. The etymological meaning of these two words stands for:

-

Esencia: nature, fundamental quality, what makes something the way it is.

-

Herencia: things that are attached.

ESENCIA FW21: moodboard

Both meanings seem to represent you as a designer. Esencia, your connection with nature and sustainability. And Herencia is deeply related to your reconstruction method and your up-cycling system of donations. Did you investigate (or know) these meanings while naming your collections? Or was it arbitrary?

I always work in logs. For Redress, I used this technique with the meaning of heritage from different dictionaries. I crossed out everything that didn’t interest me and left in view what I wanted to work on. I really like poetry. I generate interesting texts and then reread them. When I start to think, I write down all the words that come to mind to research them. I check what that word really means and relive what I consider is necessary to tell.

As soon as I arrived in the Netherlands, I wanted to make a collection that was my essence. The essence is like something present that grows, mutates, evolves and is understood. So it started like this, transmitting our own essence, like simple things.

The garments we make are the greatest simplicity that can be achieved from our essence. They are garments that last more than one season. Without too many linguistic issues, but something more simple and serene. This is how Esencia arises, interpreting us as the essence of beings. What cannot be seen but at the same time grows: the essence of people.

In the middle, when I had to present the García Bello collection in Redress, I wanted to focus on my production system, on the way of construction that I have and on the relationship with my neighbors. I inherited all that from my family, it is not something that I learned. That’s why when I won at Redress I thanked Argentina, the university and my family. That heritage they transferred to me is part of my essence, so I began to think about these related concepts. The people of Redress had a hard time understanding “Heritage-Essence, is not all the same?” It is but is not.

By winning the biggest sustainable competition in the world, do you consider yourself an icon (at least) for the Argentine fashion industry?

I think not, because I have (and know) other references in Argentine fashion. Besides, for something to be iconic, it has to transcend; it needs more duration in history and several events for people to give it this iconic value. But there are few references to sustainability in terms of fashion and I know that I am one of the best-known national designers.

I do feel that, in Tierra del Fuego and Patagonia, but especially in Río Grande -Juliana’s hometown, in the province of Tierra del Fuego-, there is great affection for me. I am the first recognized designer in my city. I also get a lot of appreciation in college. In those places, I feel great appreciation for my work and my journey.

Considering most successful designers are from Europe or the US (and they have better facilities and more opportunities), the effort behind a fashion student from a third-world country is undeniably bigger. How does it feel to be the most influential designer in Argentina, regarding sustainable fashion?

I was born in Tierra del Fuego. I share the same story with the natives and I consider myself very different from downtown people. I began to understand a lot about my own identity, how I solved problems, how I approached my work; I was very different from my college classmates born in Buenos Aires. Being from Tierra del Fuego was no small thing. My first show at BAFWeek was thanks to the Observatorio de Tendencias de INTI and I represented my province. In that experience, I began to find myself a lot and I felt the need to show another voice within the Argentine design.

“This is how we Patagonians design and feel” that was my flag, and a lot of other designers wanted to carry it too, and that was very important and nutritious to me, I felt I had company.

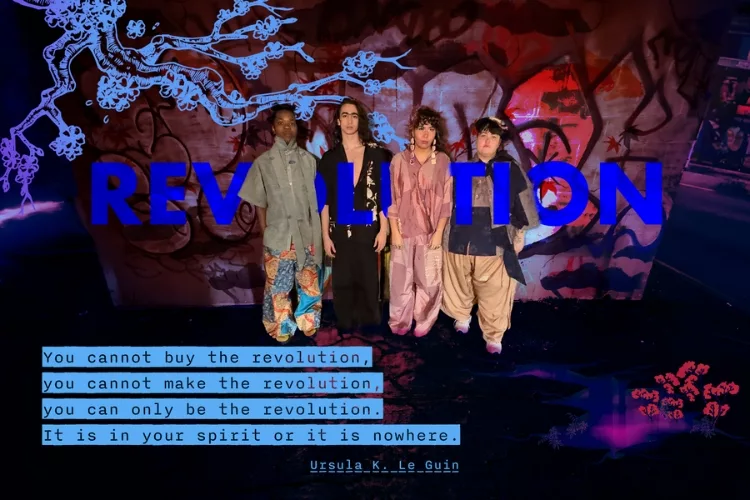

Presentation of ENCUENTRO at the Buenos Aires Fashion Week AW21

This “disadvantage” of being from inland, even from the south, turned into a virtue.

If there is a value that we Patagonians have, it is the absolute sensitivity about the place where one lives, the appreciation of nature, living in the present. A lot of things that I learned as a southerner –that connected very well with the idea of sustainability– that was beginning to spread at the time. That flag helped me a lot to value my work. Taking advantage of being born in a very small community (where you get to know everyone) made me who I am today and I work to inspire others.

Besides, you have something to tell. You can contribute something new, for people to discover.

Suddenly other people see something a little more real, close and possible. When people know my story and find out that I was raised by a single mom, at the end of the world (that kind of story that can be common to a lot of people) makes others identify and think, “I too come from a working middle class and I can also have a brand”.

It is remarkable how your silhouettes do not sexualize the female body. Plus, in your e-commerce, you don’t categorize your clothes in binary genders, just the type of garments. What motivates you to design genderless?

It comes from my past. I was an athlete in my adolescence and I liked to dress loosely, more “boyish” (based on the stereotype established by society). Because of prejudice, people assume that you are not interested in dressing up; but I’ve always been very fashionable and open about the subject. I didn’t want to give a message in which I didn’t participate. In college, I felt there was a certain differentiation in clothing. With my colleagues, we used to discuss gender, and I always interacted with people of diverse identities.

From the beginning, I understood that clothing is a cabin, and that cabin has no gender, no age, and no race. For me, anyone who wants to wear it, can. It is a flag that is important to carry: clothing has no gender.

In Redress, you could present a collection for men or women. At that time, I preferred to make women’s clothing because I am a woman and I represented women.

Juliana wearing ESENCIA

The silhouette is quite related to gender, but also the body. I am 4′ 11″ tall and generally, the clothes do not fit me and I would have to wear children’s brands. That was also a concern. I want to have on my coat rack a garment that fits me, but also a person 6′ 3″ tall or one of 240 pounds. The loose and oversize silhouette helped me to generate garments that could be used by other people in different body and height types. That kind of resolution to a larger silhouette made me solve those problems.

By choosing an up-cycling method, you are inevitably relying a lot on people donating their clothes. Don’t donations limit your work?

I work with donations and when I receive them, I do an analysis. I check their faults, why they donated them to me, if they work, etc. Then divide the garments by materiality, textile, season, type and field. This way, I am shaping my stock. I am very clear about what I want to receive: I need jeans, shirts, tablecloths and designer clothes, no more.

For the collection we are designing now, we bought deadstock. Here, some organizations are in charge of collecting raw material waste and subdividing it by size, but everything is new. They are garments that are discarded for some reason from the industry and for sale. Now we work with them because we find it interesting. In this new collection, we are redesigning Esencia based on a new system, in which we always have the material in stock and the person can also choose the combination of garments.

What other technical methodologies or sustainable resources do you use or would you consider incorporating into your brand in the future?

We offer Up-Cycling Service, where we work with other brands giving circularity to the deadstock they have within the factory. For example, we are designing a collaboration with MAIUM, a brand of raincoats made from recycled PET. We use raincoats with flaws or from old seasons. Thus with a circular and local system, we give added value to other brands that work with values similar to ours.

Here in the Netherlands, nobody produces locally; everyone produces in China and Asia. For us, it is fundamental to share our small production. Being done in the Netherlands and having only one transfer from Amsterdam to Arnhem, adds value. The production system behind it is really sustainable and brands need to begin to make visible that value.

Our garments are combined with raw cotton fibers (without dying or processing). We use this material on a small scale and with zero-waste patterns. We know that this fiber uses the most quantity of water within the production system. But at the same time, we know the cotton producers we work with in Argentina. It is a community in which we believe and support. It is necessary to maintain the relationship with the local industry because if we don’t continue betting on that production, those people will be out of work. As a social responsibility, this is the smallest contribution I can make, I will continue making, especially to the Argentine national industry.

DORA DUBA AW19: Garcia Bello’s first collection photographed in her homeland Río Grande, Tierra del Fuego

There is great emphasis on the storytelling ability of your clothing. Is this a creative strategy to create a connected community of Garcia Bello’s customers?

It is something more personal. In the search for my own identity, I understood that it was important to tell those stories. Exposing them will help others identify themselves as well. Before García Bello, I had a more artistic phase. I worked a lot in a self-referential way, and by sharing my work, I realized that my own voice spoke of other people. García Bello represents my history, the values of my family and my national and collective identity.

Garcia Bello has just been featured on notjustalabel, an online shopping destination for designer’s goods. How did this opportunity come up? Did they reach out to you?

I have been part of it since 2014 when the platform was pretty unknown. During college, I began to attend the MICA (Market of Argentine Cultural Industries), an event where many cultural agents meet for a week and offer workshops and meetings with industries from other countries. In one of the editions, I met the creative director of notjustalabel and I got to talk to him. The platform didn’t have many designers and he told me to apply. I did so with my thesis and qualified.

If you could change one thing about the fashion industry, what would it be?

To rethink a little about what we consume, for what, how long we will be using it, and what we will do with it when we no longer want it. Being responsible for our consumption is essential. In very large countries where access to clothing is so easy, for so little money and with so little visible information about the production of such clothing, people consume excessively things that they only use once or perhaps not even use. Sometimes I receive donations with new labels.

“What should change about fashion consumers is the way they relate to clothes, to be able to generate deeper bonds with what we have.”

Do you think that this change in consumption should come from consumers or producers?

It is a collective issue, not only from producers and consumers but from the governments that regulate these productions and prices, among other things. There are places where rights are not clear so certain people take advantage of this to produce there. Governments should take responsibility to set the record straight because workers usually lack support.

And I don’t think the responsibility falls solely on the consumers, either. Coming from a country like Argentina, I understand that some people need to consume clothes at very low prices. Either because they cannot afford them or they have to dress a whole family. It’s a matter of survival and not excessive consumption.

[This interview has been modified for brevity]

And A Few of Julia’s FAVORITES

Book: Mi planta naranja lima

Movie/Series: Rivers and Tides

Creative Inspiration: the steppe

Food: potatoes, in all types

Trend you like: minimalism

Trend you hate: fast fashion

Quality in a human being: the word

Person you admire: my mom

Quote to live by: breathe deeply

My collection: Cascote Abandonado

Sustainable designer/activist: Douglas Tompkins

Method to work with: Upcycling

–Nazarena Correia