How can you be a maker of things – and specifically fashion when we are living on a planet that already has too much stuff? Many creatives today are rejecting the traditional path of working for a large fashion brand. When the mass production model doesn’t align with your values how do you still manage to create? We’re meeting with makers who are creating their own paths to discover how they are doing it.

Sera Ghadaki is a Canadian born / Brooklyn based designer who transverses fashion and architecture in unexpected ways. In addition to running her own atelier she is a founding member of WIP Collaborative. WIP (meaning ‘Work in Progress’ and ‘Women in Practice’) is a shared feminist practice focused on research and design projects that engage community and the public realm.

The process of taking something from an idea to an actual thing that you can wear or a space that you can walk through. These were all laying the foundation for what I’m still interested in.

No Kill Mag: Hi Sera, thanks for meeting with us! We’d love to learn about your work’s evolution. Your main formal education has been in architecture and interiors but you design in fashion. So how do you situate your work within that space?

Sera: I became interested in fashion design during high school–teaching myself to sew when I was fifteen. It was a way of self-expression and to counter mass-produced clothing. The “making” part as well as patterns and geometries were my interest. I decided to attend a fashion program in Toronto to hone my skills in pattern making and see if this is what I wanted to pursue more seriously. And quickly realized I love this craft, this work.

But I also saw the challenges of a traditional fashion career. The primary options in Toronto at the time were working for a big heritage brand, or becoming a technical designer. I knew I wanted more independence, to make my own rules (in fashion). And that doesn’t always equate to making a full time living! Architecture was another design discipline I was interested in. I realized I could apply everything I enjoy about fashion, the connection to people and bodies and feelings, on a larger architectural scale.

How did you go from fashion to architecture?

I was on a shoot as a styling intern and told the photographer that I was applying for university and he suggested environmental design at OCAD (Ontario College of Art & Design University) –which I did and was accepted. We were immersed in interior design, architecture, and sustainability –designing for the built environment. It really opened up my eyes to thinking about design as a multi-disciplinary entity. It was there that I started my eponymous label to sell my own clothes and design collections. Doing so while still in school and in a highly creative, experimental environment felt liberating.

Then, when I was graduating and looking to apply to Master’s of Architecture programs, the Chair of the program recommended Pratt. He felt that with what I was interested in, Pratt’s architecture program would be a great fit. Especially with my fashion background. I always included fashion work in my portfolio to emphasize the interplay between clothing and the environment and how I bring those principles together.

How does WIP complement your own practice?

I have always wanted to collaborate with like-minded designers that have multi-disciplinary backgrounds and interests. This was hard to find at a more traditional architecture firm where the work –and your tasks– can become homogeneous. With WIP, in addition to being a shared practice, we work in a non-hierarchical manner and embrace our diverse backgrounds and experiences. To me that is a huge strength and liberating way to work-a group of women that have come together to work on shared projects. It’s very much a work in progress. That’s the duality of our name – it stands for Work in Progress and Women in Practice because we embrace that there are some aspects of how we work together that we continue to figure out.

Has this influenced your personal working practice?

Yes, I’ve become more open to sharing the in-progress parts! Often with design, architecture or fashion what you see is the final result. You see the runway, the building, the product shots, the editorial. You don’t see the messy parts.

Working as a solo designer means that ideas often get stuck in my head, on paper or are partially completed. So I’m kind of embracing more of the “in process nature” of posting something online and saying “coming soon” or posting a piece of clothing that’s not totally completed.

I find something empowering in that. That you can take control of the situation and it doesn’t have to be completely polished and on a model with professional photography.

And people respond to that –the behind the scene things.

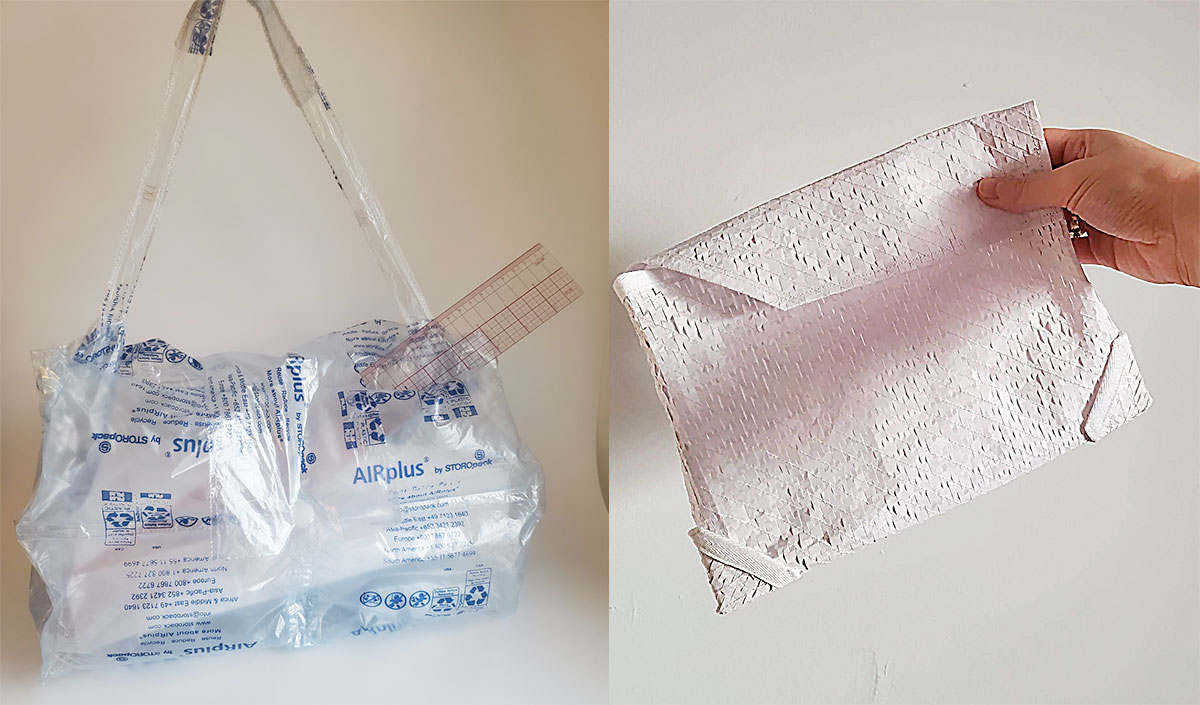

Talking about “imperfect” leads me to impermanence which makes me think of that bag (gesturing to the air bag) which is really cool. Is this one of the things you’re selling? I have to say the impermanence of it is part of what makes it intriguing.

The Airbag stemmed from a very simple limitation to make a functional piece out of packaging material that is designed to be thrown away, so the aspect of impermanence is very intentional in this instance. On the product page there is a note that the bag is meant to hold lightweight objects under one pound and that the inflatable components may deflate over time, but that the bag will still be usable.

When you do pieces like “Airbag” or “Texture as Pattern”, is it more conceptual/experimental? Or do you find that the materials can lead to an ongoing resilience and recyclable product? Or is that important to you?

I love doing these experiments. I get packaging and it’s kind of an organic thing. These are very much products of the pandemic – I’m using what I have, my sewing machine, thread and materials I already have, and reusing packaging material is another layer to it. It has made me more aware of materials and objects that have a very short function lifespan. These air pillows, for example, I never thought about before.

But I thought let me use this material to create something that has a secondary function, and really try to extend its life cycle. So yes, I would absolutely love that this becomes more of a more viable product, but it has a research component of adaptive material reuse too.

To me, the big issues that the fashion and architecture industries share include materials and waste. Finding a solution that could bridge these two industries intrigues me. I know it’s been done – like denim insulation for example. That example – it’s always in my head – how can there be some kind of different or alternative way of recycling materials? For example, transforming fashion waste into an architectural product.

This is definitely something I would not be able to do by myself. It’s something larger than me but on my mind for a number of years. How can all the disparate things come together? And combine in a way to impact people and the planet? But coming back to Airbag, Texture as Pattern, and future object-scaled experiments, while these are still quite conceptual, they are also for purchase and intended to be used as a functional object. But it’s up to you to use it however you want.

That’s what it felt like – ‘I’m offering you the idea if you want to enter into the conversation.’ and that felt fresh.

Tell us about Ghost Bodice because it’s really beautiful. Do you see that as evolving or was it a one off?

Actually, I’m in an evolution of that. Ghost bodice was my final project in graduate school. It was a really great discovery of how to create a production technique informed by different disciplines. To give a little more context; that project was from a course that started by analyzing SEM scans of microorganisms and taking that from a diagrammatic but also conceptual way and I went with it.

As my final project, I really wanted to experiment and I discovered a process and was inspired by Frei Otto’s work with tensile structures and research into wet thread models. With all that in mind it was a lot of playing and I had a lot of thread and I figured out a way to just dip glue – it was very low tech! The ghost bodice was entirely made of watered down glue….

Really? It looks like something that could have been 3D printed!

It just was bobbins of white thread.

Brilliant

I was in my studio apartment making things up as I went, and the process ended up being paper mache but with thread. The first time I used a balloon as a form and then next a dress form bodice. It was an idea that stuck with me. How to create this delicate, ephemeral material that could be worn?

So this is my most recent iteration of it. An experimental top.

I took what I loved about that project –I was literally taking a bobbin and taking the thread off of the bobbin and thought, well that’s wasteful in itself. I have a bag of little shreds of fabric that I have been collecting from production scraps for a while. But thread waste is something that is not typically considered to reuse, it’s usually textile waste which is reused.

Wait ‘til this No Kill article hits, thread waste is going to be all the rage!

I would absolutely love that. When I interned for different designers, thread was everywhere. It mixes with hair, it mixes with dust, it’s like a salon and you have to sweep it out. I began to gather thread scrap from the floor of my studio and kept collecting until I had enough to create something else from it.

The process of this is that I started with dissolvable interfacing (no glue!) this is from production off cuts…

You have absolutely no idea what will happen…

I have no idea.

This is so exciting it’s a completely process driven outcome…

I actually repeated the “quilting” step twice because it was too delicate.

Can you talk about the convertible vest?

I really love the idea and the geometry of the shopper totes that you get at a bodega now that there’s a plastic bag ban in New York. I love that they’re so simple. It’s almost one piece but pleated and cut so there’s a little bit of structure. I took one and studied it a lot.

I made a piece a number of years ago called the Zip Jacket. It had one continuous zipper at the waist so that you could zip the bottom half of the jacket off to create a cropped coat. This concept was an evolution of that idea so I call this the Zip Tote. In this form, it’s a tote bag. And then you can literally unzip it, unfold it and wear it as a vest.

You can wear it in a few different ways. And what I really loved about this material is that it’s thermochromic.

Which means?

It is temperature sensitive and it reacts with body heat. So this one, when you crinkle it, you start to see these light blue marks like crumpled paper. And then when you iron it, it’s completely solid again. Even if you start to stretch it, you can see that it turns light blue as you wear it – it’s meant to show the wear in a way. And I don’t like to iron things. So it’s also a way of celebrating wrinkles.

How would you define yourself if someone asks? Understanding that this can be limiting but …Nowadays I’ll say the very obvious. I’m a fashion and architectural designer and I think people find that compelling. There’s an open-endedness to it.

How do you position your work within relation to climate, as a storyteller?

I love that. Let’s see what story? The story I could start with is I do believe that we don’t need any more clothes. That is a fact. We don’t need any more things on this planet. So it’s very much about creating things with purpose. But it’s not just that.

It comes back to challenging fast fashion and mass production. It might not make a lot of sense as a business model –using deadstock materials or found materials that aren’t easily re-ordered. And really experimenting and playing and challenging fashion as a business and seeing it more as an art form that can be worn.

It’s the art form part of it that’s important for me – that pieces are made in very small limited quantities, are made-to-order, and are often one of a kind.

photo by Abby Hassett

As I consider climate and renewable and regenerative ideas, it only makes sense to try to reuse one-time-use materials. I simply don’t want them to go to waste. I like the material and I want to see its capabilities. And as an independent designer, I only wish to make something someone will be buying. I want to create something that is going to be used.

I truly believe in the power of numbers here, and that these ideas and impact can multiply with every designer that makes a decision that is centered around combatting material waste and producing in a more conscious manner.

What are your future plans/intentions?

My intention is to grow my independent practice, to work simultaneously on projects and to develop this into a viable thing where I could sustain the work and also collaborate with a team. I want this to be larger than something that I could do by myself.

Sera Ghadaki’s Website | Instagram

–KL Dunn + Katya Moorman

Related Articles