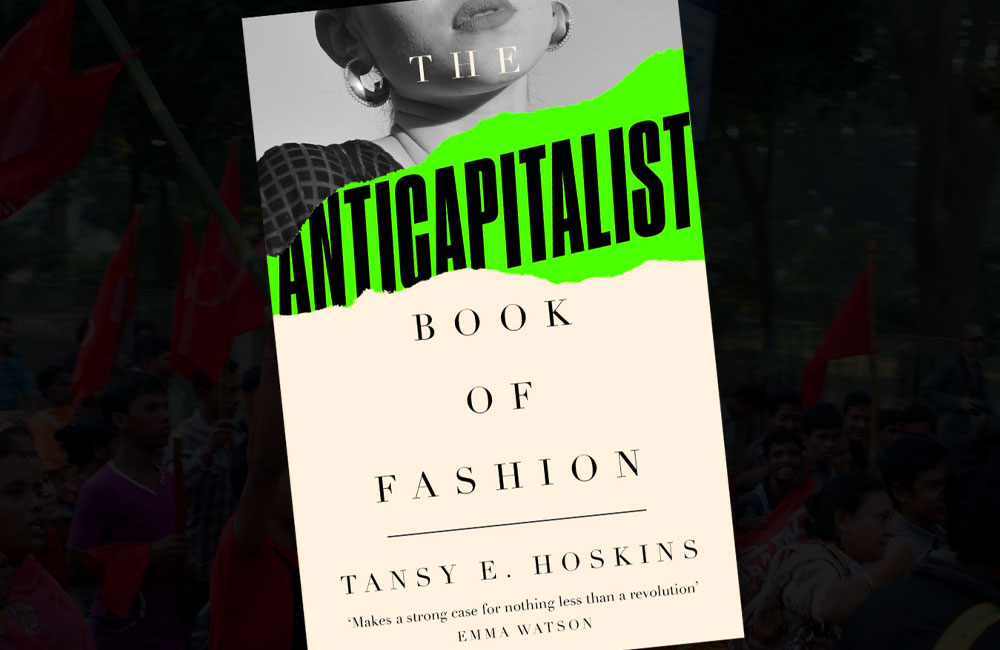

Tansy Hoskins wrote Stitched Up in 2014. The book was a fresh and radical take on fashion and capitalism, destruction and resistance, climate and land, billionaires and workers. It addressed two big questions: what is fashion and what is it for?

Eight years, a pandemic, a digital media revolution, and countless climate disasters later, she felt the book needed an update, and in the process she rewrote much of it.

The Anti Capitalist Book of Fashion echoes the themes of its predecessor while placing them in today’s context. The central message remains defiant: if fashion is to survive, capitalism must go.

What is Fashion For?

Hoskins posits that fashion can be one of two things: a means of dressing society in well-made, well-designed and durable apparel, or a system of exploitation to make profits for business. She shows how, at different times in history, fashion has served both functions. Today, however, the latter dominates, and that is the problem.

Fashion – which Hoskins defines as ‘the changing style of dress and appearance adopted by groups of people” – has a symbiotic relationship with society. Culture shapes both which fashions are produced and how they are received. During World War II, for example, resources were scarce and everyone was pulling together in a joint enterprise–which yielded utilitarian and egalitarian designs. When the common enemy was defeated and society stratified once again, fashion was there to reinforce the polarization. Notably starting with Christian Dior’s New Look. Lavish use of luxurious fabrics brought fashion back to its days as a class signifier, something afforded to and enjoyed by only a select few.

The transition was sped along by what Hoskins calls the Fashion Media, which includes everything from 300 year old magazines to contemporary Instagram influencers. The Fashion Media caters to its two sources of revenues, readers and advertisers, creating an editorial environment that consumers want to visit and advertisers want to buy space in. Because it’s beholden to sponsors, content is skewed towards fawning profiles and breathless product reviews – what Gloria Steinham aptly termed “complimentary copy.” Devoid of substance or critique, most of it is concerned with one simple goal: getting readers to buy things.

Despite being at the mercy of corporate capital, Hoskins says, the Fashion Media are not victims. Instead they are complicit in perpetuating the myth that beautiful clothes rely on the current fashion system, which is fine and can continue forever. There’s no disagreement on this point among them, and there’s a reason for that. Fashion Media is generally conceived of as a set of magazines: Vogue, Glamour, Elle, Bazaar, Grazia, Allure, Vanity Fair, etc. Today, all of them are owned by a pair of interchangeable corporate giants – Condé Nast and Hearst. And no matter who is singing, we’ve heard this song before. Surface diversity covers up increasing consolidation. Rebellions get co-opted. And the result is always the same: another pricey it-bag to throw in the closet (and eventually the landfill).

Co-opting Disruption

In the 1970s, punk challenged the aesthetic values of the dominant classes. Vivienne Westwood and Malcolm McLaren rejected bourgeois convention across the board. But it didn’t take long for the fashion industry to co-opt punk style and commodify it. The same happened with grunge. When Marc Jacobs sent models down the runway wearing flannel and combat boots at the Spring 1993 Perry Ellis show, he was fired for his presumption. Soon after, the fashionistas embraced the trend, prices shot up, and another set of outsiders was absorbed into the industry’s maw.

The system doesn’t want to change, so it invites its rebels into the fold, ignores their critiques, and aestheticizes their disruptions.

Today this story is playing out with sustainability. Aware that fashion is increasingly considered to be destroying the planet, the industry is keen to distance itself from the charge and attempts to associate itself with solutions. The term sustainability is used so broadly and promiscuously these days that no one knows what it means anymore. It’s been reduced to a marketing ploy. An invitation for virtue signaling by buying a fresh set of “sustainable” things–which aren’t even really sustainable. Hoskins points out how H&M’s Conscious Collection actually contained more virgin synthetic fabrics than did the 47 other collections it featured last year.

Capitalism’s Favorite Child

The book concludes that the only way to save fashion is to abolish capitalism. Our economic system, she argues, is shot through with contradictions, crises, injustices, inequality, and exploitation. And the fashion industry is rife with all of that–”capitalism’s favorite child,” it has been called. To her credit, Hoskins goes beyond critique to offer an alternative. Although not an entirely convincing one. She proposes a sort of workers’ utopia, where there is no private property and everyone owns everything in common. (Think Rent the Runway without the rent, but we all made the clothes ourselves too.)

Hoskins’ solution relies on radical mass mobilization, a collective overthrow of the fashion mafia and greater corporate powers at large. In the process, it negates the value of individual agency. Fashion will continue to co-opt culture, she argues, including resistance culture. Today environmentalists throw soup on paintings to call attention to the climate crisis. Next year, H&M will probably have some soup-splattered Mona Lisa t-shirts available for purchase, and wearing one will substitute for action.

Hoskins makes her case for collective action by suggesting several organizations to get involved with. You can find them listed below, and they’re all doing great work. There’s a lot about the industry that needs changing. But she may be both too optimistic and pessimistic. Capitalism isn’t going anywhere anytime soon, we need to subvert it in whatever way we can. And while our individual choices may not necessarily aggregate easily into radical change, they aren’t nothing, either. Defining your own parameters of what better fashion means for you is the place to start. It can orient your style and your consumption along with your activism, giving life to your style as well as style to your life.

International Labor Movements: Get Involved

This list is by no means exhaustive, but serves as a starting point for learning about organizations working to fix fashion

Asia Floorwage Alliance

Garment Worker Center in Los Angeles

Solidarity Center

Workers’ Rights Consortium

Clean Clothes Campaign

Labour Behind the Label

War on Want

UniGlobal

IndustriALL

-Steph Lawson

RELATED ARTICLES

What Exactly Is Sustainable Fashion? We Asked an Expert

It’s Not Fast Fashion vs. Sustainable Fashion but this Instead

Why I Signed the Open Letter

5 Books to Increase Your Sustainable Fashion Knowledge