You wouldn’t think a book about chemicals in your clothing could be a “page turner” but you’d be wrong.

photo: our copy of To Dye For full of notes on our “laptop desk” (aka cardboard box). with our “assistant” (aka dog Phin)

–KL Dunn

Like most kids, I fought with my mom over clothes – not about hemlines or styles but colors and materials. As a working mom with active kids, she bought into the ease of poly-blends –wrinkle/carefree/stain resistant. But something about the feel of these fabrics rubbed me the wrong way. As for bright colors, well, not my thing. I only wanted 100% cotton –the stuff that wrinkles after the wash. So we fought about it, but then she taught me to iron and let me wear whatever made me happy.

But my battles weren’t over. There were white-knuckle disagreements with my tennis coach. As the team captain, she expected me to wear the new uniforms. They were “smart,” they were “sexy,” and they were so fu**ing uncomfortable and stinky. So I continued showing up to practice and matches in old cotton shorts and my dad’s holey cotton sweater. Fast forward to now. I don’t iron as much. I’ve expanded my wardrobe to wool, cashmere, and hemp – all single fibers known as natural textiles. But this article isn’t “confessions of a queer’s fabulous organic fashion journey”. Instead, it’s about what I’ve learned about materials and toxicity from Alden Wicker’s To Dye For: How Toxic Fashion Is Making Us Sick–And How We Can Fight Back. Funnily enough, it all starts with uniforms.

Flight Attendants Battle the Airlines

This book, in many ways, tells the story of how our clothes are killing us by being able to focus on a perfect test case: flight attendants. When we think of flight attendants we first think of those chic, early Pan-Am flight attendants. And then remember the age and size discrimination and decide perhaps not-so-chic –or certainly unacceptable by today’s standards. But while there have been some improvements in diversity flight attendants have a new battle on their hands: toxic clothing.

As we learn in To Dye For, employees from major airlines such as Alaska Air, American Airlines and Delta have become ill from wearing their uniforms. They are working in tight quarters for long hours, wearing the same items for days on end. And these are coated with chemicals to make them wrinkle and stain resistant with colors that pop. But those “benefits” have health costs that include everything from skin rashes to breathing problems and worse. One story follows another of flight attendants getting sick. Yet many won’t report their illnesses for fear of reprisals. And those who come forward are initially dismissed as overly sensitive.

“There are next to zero regulations for chemical content of clothes in the United States,” according to the lead investigator in the airline scandal Judith Anderson of the AFA (Airline Flight Attendants).

image of uniform rash

As she continues her research Alden asks, “How could we know so little about something that plays arguably the most intimate role of any consumer product in our daily life? The textiles and materials that caress our most private body parts have become duplicitous: beautiful and alluring, yet dangerous. Only the faintest clues – a whiff of caustic odor here, a disconcerting bright color there, a plasticky hand feel – hint at their true nature”. And that they are an invisible menace, infiltrating our air, water, homes, and bodies. “There’s a term now for the invisible world of synthetic chemistry that lives inside us: the human toxome.”

The problem with synthetic fabrics is less the fabric itself and more the chemicals it is treated with to give it that Color and performance.

In To Dye For, we learn that something called Azo dyes are used to dye synthetics the colors we want. Twenty-two Azo dyes have been banned in the EU. Why? Because they have been proven to be carcinogenic and have mutagenic properties when they come into contact with our skin bacteria. Translation: these dyes not only cause a myriad of cancers but mess up our endocrine systems. But they are still legal in the US and other countries that manufacture our clothing.

When Wicker asked a leading chemist about alternatives, he explained that other options were also toxic. And went on from there, “I’m not aware of any dyes that can be used to color synthetic fabrics that aren’t risky from an exposure standpoint.”

Sit with this for a minute. All of your colorful leggings, sports bras, and tees are likely treated with chemicals that can make you sick. This begs the question: wouldn’t companies ensure their products are safe for humans? Yes…and no.

A large part of the problem involves mixing chemical compounds. And unbelievably, the chemical combinations on a single garment aren’t studied. So if chemicals A, B and C are all at their own “safe” levels a product is deemed safe even though in combination we don’t know what the results will be.

And while we don’t wear the same thing day in and day out like a flight attendant there is evidence, according to To Dye For, that points to multiple health issues linked with what we wear. Are you inexplicably tired? Having a hard time getting pregnant? Perhaps you’ve been experiencing unexplained heart palpitations, or have developed unexplained thyroid issues. The list, unfortunately, is long and while women may have more sensitivities leading to a significant rise in infertility rates, what grabbed worldwide attention was falling motility (sperm) rates.

Of course because we know so little about the chemicals we wear (this is intentionally kept from us as “trade secrets”) it’s hard to prove the link between our clothes and our health. But it’s hard not to see how this is a logical conclusion with all of the facts presented.

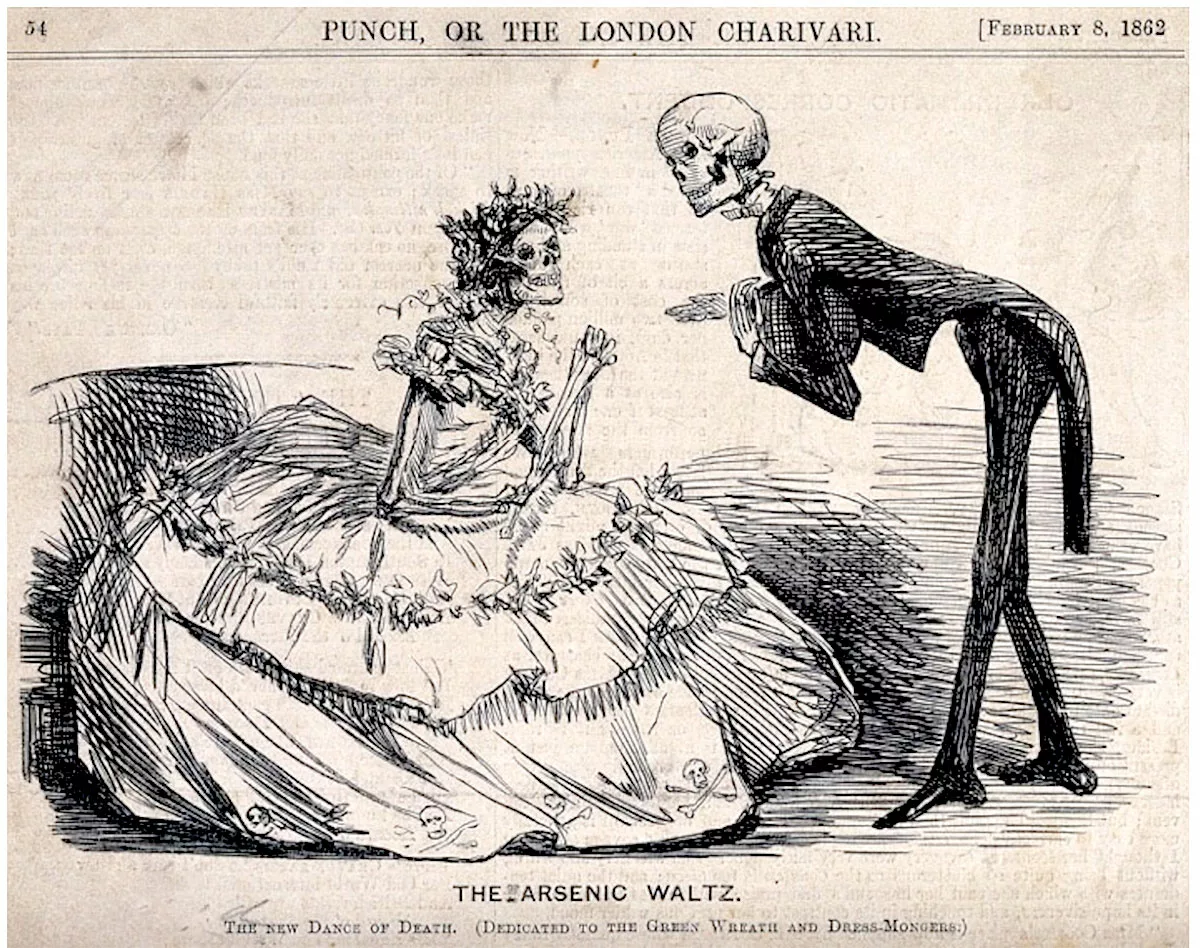

The chemical compounds may be new, this “trend” is not.

Wicker delivers an impressive history lesson on how toxic many fashion practices have been. She reminds us that Alice’s Mad Hatter in Wonderland was mad precisely because of his hat – which contained copious amounts of poisonous mercury like most stylish headgear of the nineteenth century. Over 100 years earlier, in 1716, the French hatters’ guild (similar to today’s unions) outlawed mercury. But by 1751, commercial pressures caused legislatures to cave, and again they legalized its use. “Fast fashion was already forcing its way into Europe.” Alden Wicker writes. It took until 1941 to finally ban the use of mercury in hat making!

The most grotesque and consequential tale concerns copper acetoarsenite and the color green. With its discovery in 1814 as a truly radiant hue, the brilliant saturated greens ruled fashion in Paris and London. And the flowers dipped in the dye adorned Europe’s “most fashionable heads, hats and frocks.” But it took an “accidental” yet highly publicized gruesome death of a young flower maker to ban the pigment from commercial use. Her name was Matilda Scheurer – it took her a long time to die – still, the jury at the inquest called it accidental ‘occasioned by arsenite of copper used in her employment.” And instead of blaming the (male) workshop owner of the (male-owned) dye manufacturers, the journalists of the time blamed the women who fell for the products.

Wicker points out the similarities today where micro-influencers are shamed for tagging fast fashion brands while the public ignore the male founders of these same brands who hide from media attention yet “consistently rank in the top twenty of the world’s wealthiest billionaires.”.

So what is the true cost of the chemicals on our clothing? Because “unlike food, beauty, or cleaning products, clothing doesn’t come with an ingredient list.” If it did, we’d probably walk around naked.

To Dye For leaves the diligent reader with a list of “to-do’s” and a way forward. These include:

- Avoid cheap knockoffs and unknown brands, and what should be the easiest, fast fashion.

- Find companies you trust. I know this one is difficult, but I like that Wicker suggests only buying that blouse that you could cradle-to-cradle compost – one that wouldn’t poison your organic garden (ok – we don’t all have one but come on, people, use your imagination).

- Always wash clothing before you wear it.

- Buy second-hand or swap.

- Trust your nose – if it smells of chemicals, don’t buy it!

Pick up and read a copy of To Dye For. It’s a thought provoking read on how the toxicity of our clothing is making us sick and offers ways forward to make change. Part history, part expose, Wicker brings much-needed visibility to the dirty truth behind colorfully dyed, carefree fabrics. Earth-shattering and entertaining, the book is a “crie de cœur” about how the $2.5 billion a year fashion industry escapes scrutiny, bringing illness and leaving ecological havoc and what we can do to change this.

Related Articles

- It’s Time to End Our Toxic Love Affair with Synthetic Clothing.

- There’s WHAT in my underwear?

- You Deserve Better Than Fast Fashion: An Interview with Amanda of Clotheshorse Podcast

- Meet Rosie Broadhead, the Futuristic Designer Making Clothes with Skin-nurturing Probiotics

- Fossil-free Activewear: How to go from oil-based to natural fiber

- It’s not “fast fashion” vs “sustainable fashion” but this instead…