On what would be her 100th birthday, Diane Arbus’ work continues to speak to the current cultural moment.

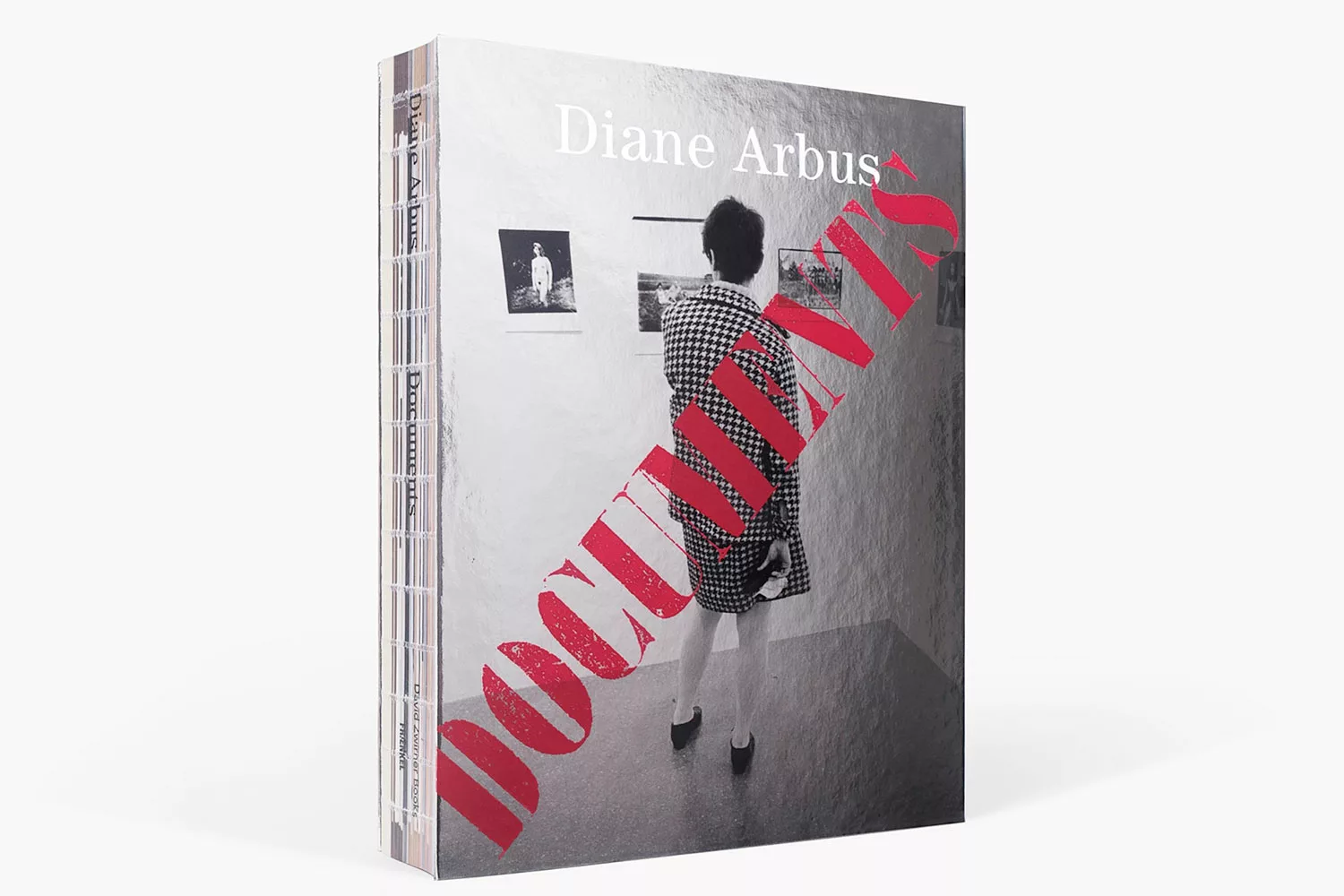

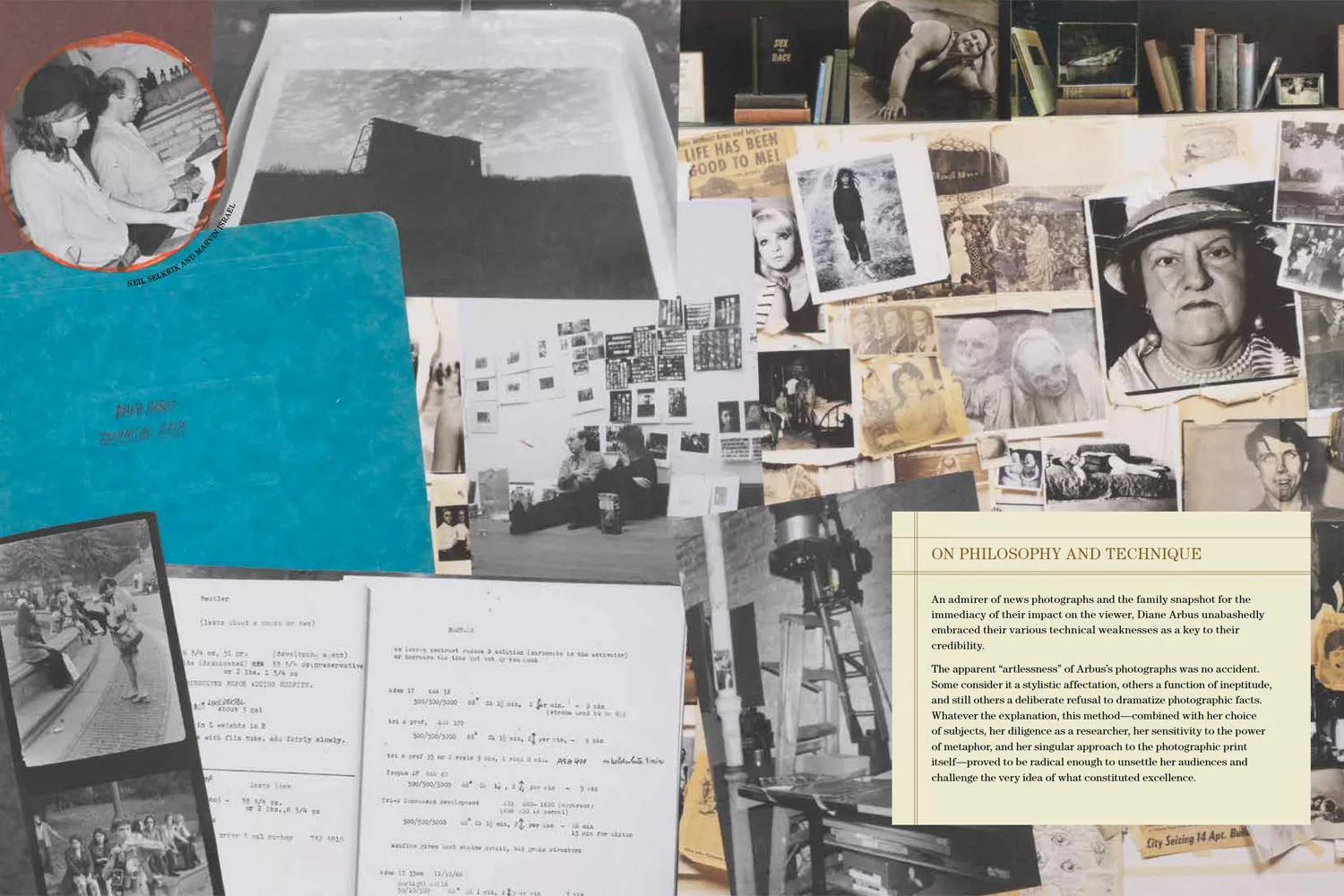

While one expects a book about a photographer to be mainly a book of photographs, this unusual and offbeat publication, Diane Arbus Documents confounds what’s normal much in the way she did herself. It is described by the publishers, David Zwirner Books and Fraenkel Gallery, as a tale of two books. One of her work –radical, upending social niceties, breaking our collective understanding of what a photograph is– and the other, 50+ years of unceasing argument about what her work means. Edited by Max Rosenberg and designed by Yolanda Cuomo and Bonnie Briant, it is an explosive and expressive attempt to “create” Arbus for the reader/viewer.

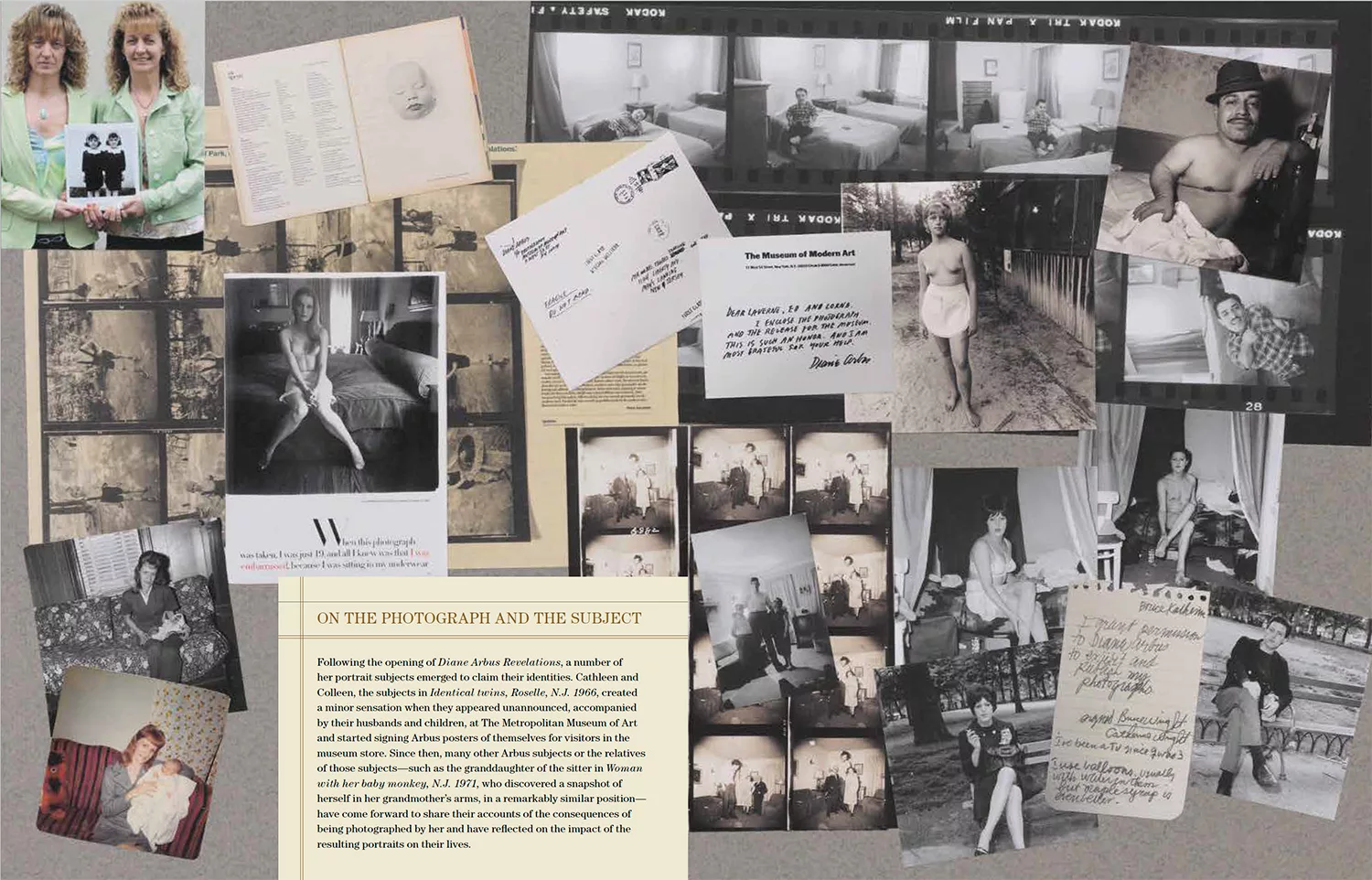

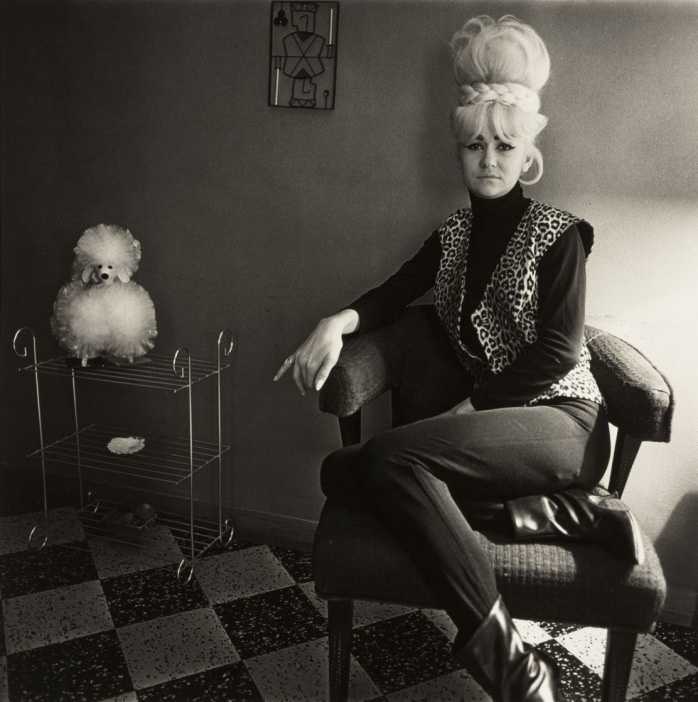

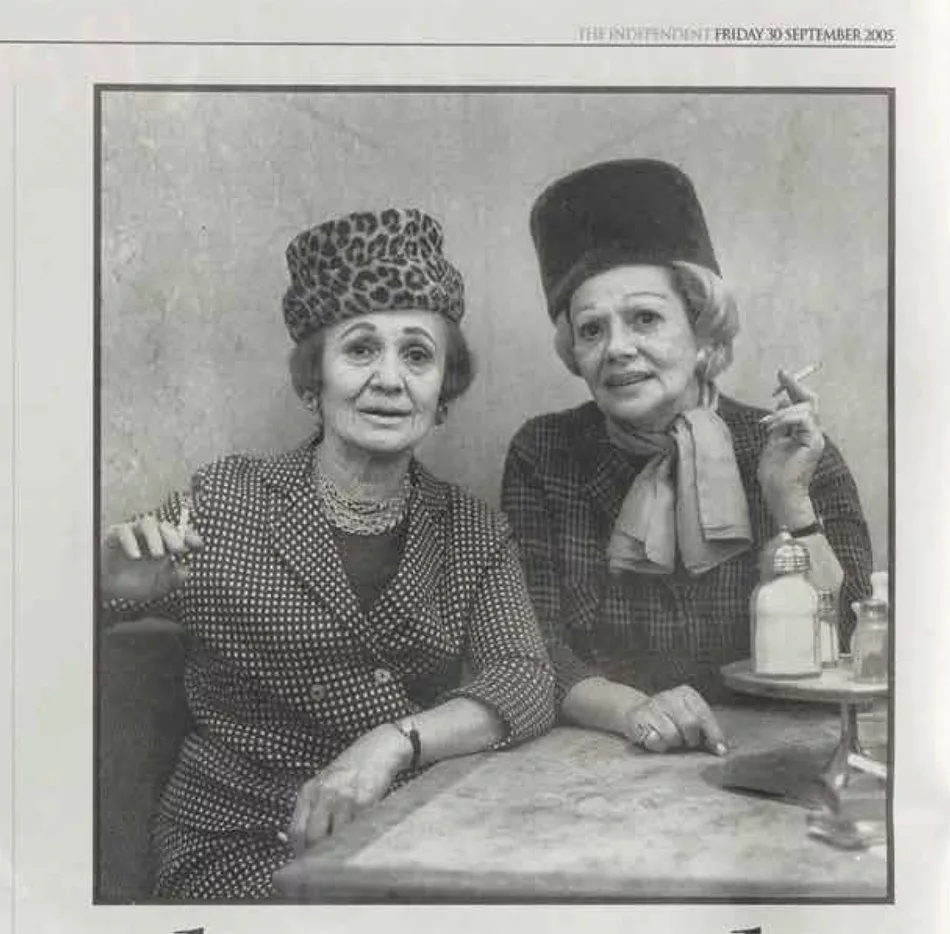

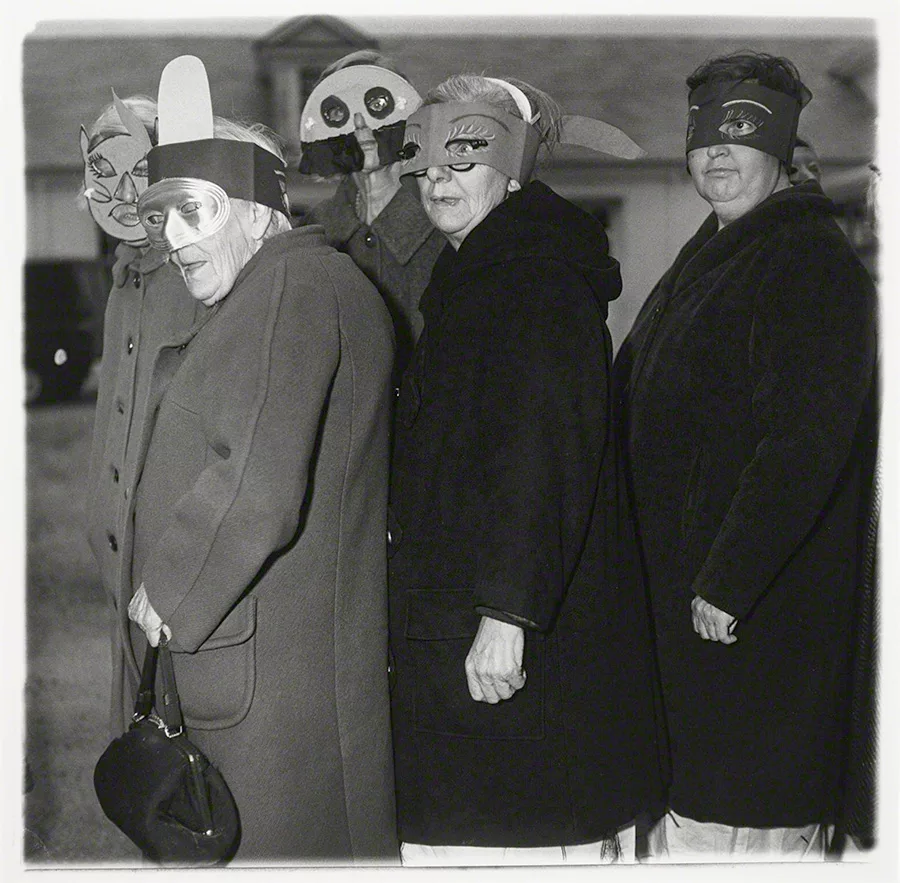

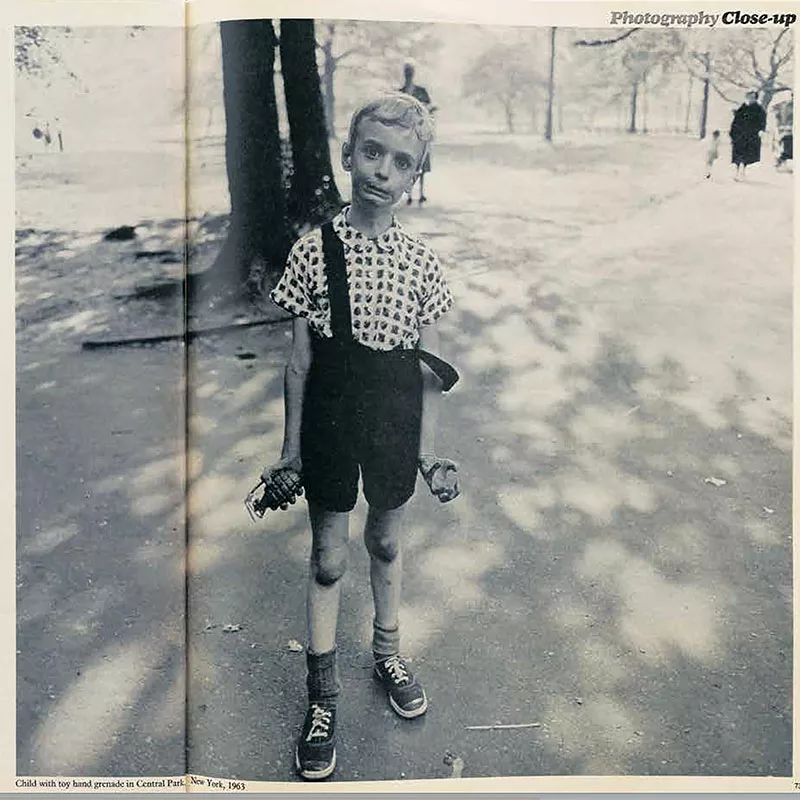

Diane Arbus’ dream was to photograph everybody in the world. So between the “divineness in ordinary things” and freaks, she was famous for seeing and asking us to find our humanity. Her ability to see the outsider as worthy of our consideration perfectly aligns with this moment where again marginalized groups are being militantly dehumanized. It’s almost hard to imagine how radical her work was when it first came into the public eye.

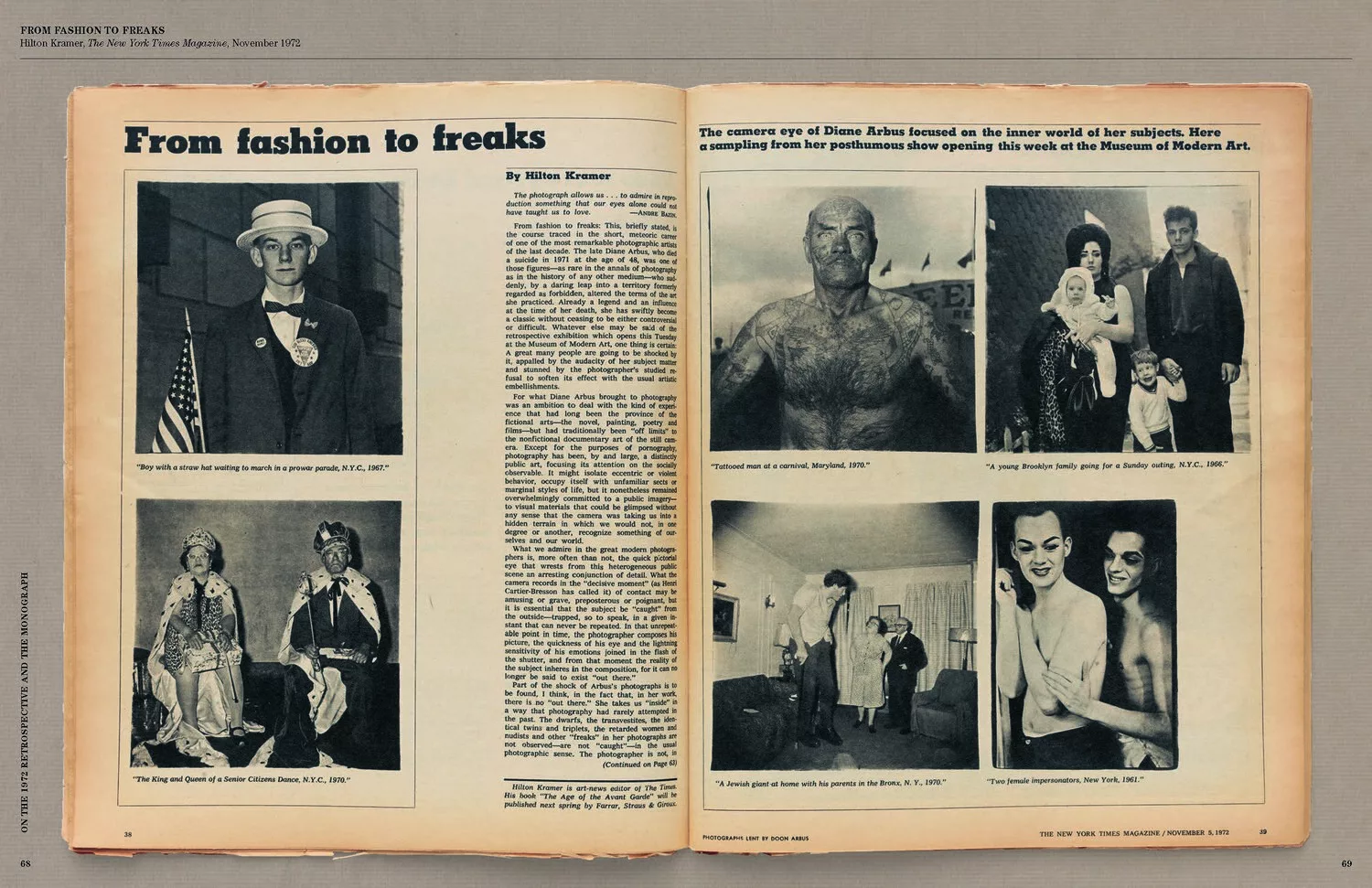

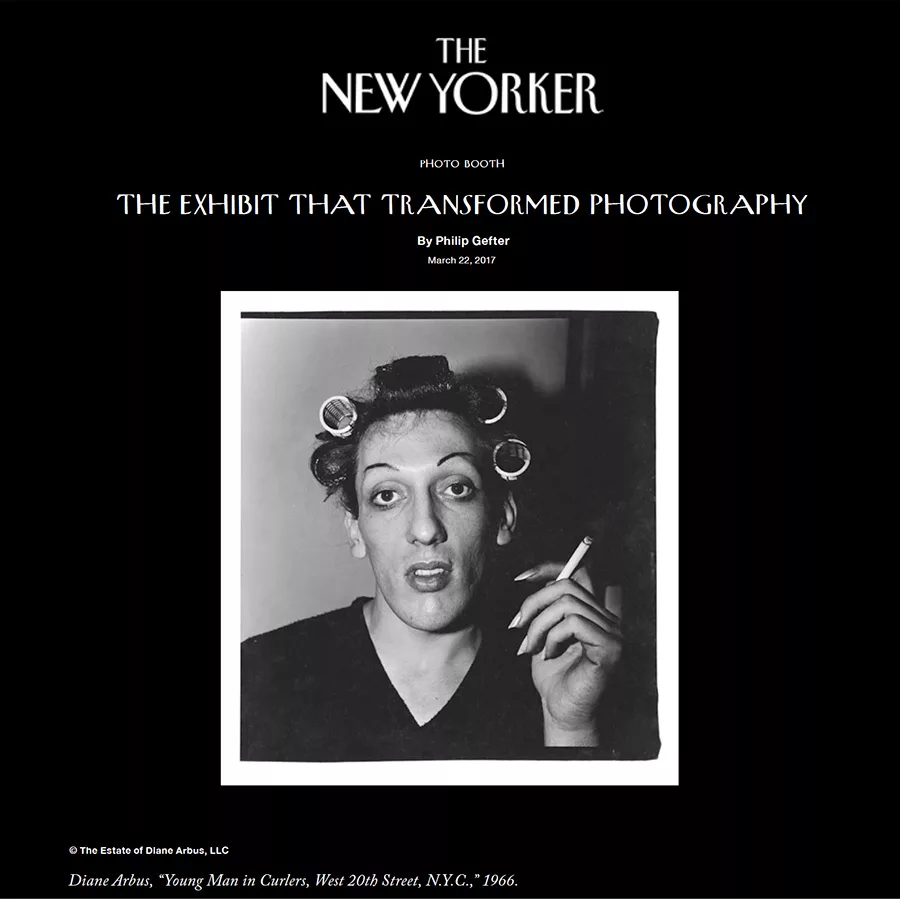

Robert Hughes, the Australian art critic, wrote of her MoMA 1972 retrospective, the year following her death “Arbus did what hardly seemed possible for a still photographer. She altered our experience of the face.” For while a photograph is fixed, its contents cannot change – only our perceptions and understandings remain fluid.

So in a publishing sleight of hand, critical writings in conflict with one another are presented and mirror their cultural moment in time. Is Arbus monstrous and exploitative? Is she genius? There is a graphic tension and delight and dialogue made possible while 50 years of art criticism and journalism compete within the cover.

Like haute couture, the original volume was a handmade spiral-bound reference (12 copies were made for traveling to exhibitions) that wasn’t initially intended for publication. No one involved believed the copious copyrights could be cleared; but they were, resulting in this volume. It stands as a testament to this formidable artist on her 100th birthday. The publishers suggest that while ” history is more often the product of what is said then of what occurred, Diane Arbus Documents is intended to stimulate deeper study, and perhaps less-ready judgment of her inexhaustible achievement. It may also lead to second thoughts about” how her work is understood. 50+ years after her death, this sensitive photographic intelligence still asks complex questions that will “spark the fiercest battles.”

On Diane Arbus

ON A FORETASTE OF ETERNITY:

Confronting a major photograph by Arbus, you lose your ability to know—or distinctly to think or feel, and certainly to judge—anything. She turned picture-making inside out. She didn’t gaze at her subjects; she induced them to gaze at her. Selected for their powers of strangeness and confidence, they burst through the camera lens with a presence so intense that whatever attitude she or you or anyone might take toward them disintegrates.

The image starts to affect you before you are fully aware of looking at it.

Its significance dawns on you with the leisureliness of shock, in the state of mind that occupies, for example, the moment—a foretaste of eternity—after you have slipped on an icy sidewalk and before

you hit the ground. You may feel, crazily, that you have never really seen a photograph before.

—Peter Schjeldahl, “Looking Back,” The New Yorker, March 21, 2005

ON METAPHORIC LANGUAGE:

Throughout Arbus’ work the most deceptively simple photographic facts embody a kind of literature: riddles, fables, Freudian slips and the kind of metaphoric language that belongs to dreams and nightmares. No photographer before or since has made the act of looking an act of such intelligence, that to look at so-called ordinary things is to become responsible for what you see.

—Richard Avedon,

quoted in Abigail Foerstner,

“Diane Arbus Demystified Celebrities, Celebrated the Taboo,” Chicago Tribune, February 15, 1991

Words By Diane Arbus

ON FREAKS:

There’s a quality of legend about freaks. Like a person in a fairy tale who stops you and demands that you answer a riddle. Most people go through life dreading they’ll go through a traumatic experience.

Freaks were born with their trauma. They’ve already passed their test in life. They’re aristocrats. If you’ve ever talked to somebody with two heads you know they know something you don’t.

ON DIFFERENTNESS:

This is what I love: The differentness, the uniqueness of all things, and the importance of life. . . .I see something that seems wonderful; I see the divineness in ordinary things.

—November 28, 1939, at age sixteen, essay on Plato

ON THE GAP BETWEEN INTENTION AND EFFECT:

You see someone on the street and essentially what you notice about them is the flaw. It’s just extraordinary that we should have been given these peculiarities. And, not content with what we were

given, we create a whole other set.

Our whole guise is like giving a sign to the world to think of us in a certain way but there’s a point between what you want people to know about you and what you can’t help people knowing about you. And that has to do with what I’ve always called the gap between intention and effect. I mean if you scrutinize reality closely enough, if in some way you really, really get to it, it becomes fantastic.

–KL Dunn

Related Articles