–by Christine Deleon

Finding expression at the intersections of fashion, South Asian community and queer culture

London designer Rahemur Rahman came onto my radar in 2022 at the Victoria and Albert Museum’s Fashioning Masculinities exhibition. He is the first Briton of Bangladeshi descent to be represented in the V&A’s permanent fashion collection. This inclusion in the permanent collection is of immense cultural importance, especially considering the colonial overtones associated with the V&A. The museum’s permanent collection houses colonial Britain’s ill-gotten spoils — Bangladesh’s cultural artifacts were no exception.

The Bangladeshi community Rahman hails from was also at the heart of the British rag trade, which, in the last quarter of the twentieth century, centered in East London’s infamous Brick Lane.

Pushing boundaries: estates and education

Rahemur spent his childhood summers visiting the Boundary Estate at the top of Brick Lane with family and friends. At the time, the housing estate was dynamic and alive, with young children playing out in the street and their Nanis keeping a close eye on their grandkids. There was a strong sense of community back then, but as time has passed, gentrification has transformed the landscape: Nudie Jeans, Sunspel, and Folk all have shops here, and the exclusive club Shoreditch House is literally across the street.

However, back in those heady days of the early 2000s, the Bangladeshi community lived next to Banksy’s graffiti and the Whitechapel Gallery where the seminal US artist and activist Nan Goldin held her first major UK show. It was in this dynamic mishmash of immigrant communities, street culture, and LGBTQIA art that Rahman happened upon a community engagement project that inspired him to study fashion design at Central St. Martin’s.

I would say the trajectory to St Martin’s became a thing, because they had a tutor there, and he was just like, you’re good. If you work a little bit harder, you can be even better.

Not one to rest on his laurels, Rahman left St. Martin’s and, in 2019, launched his first collection influenced by his Bengali roots and the East London rag trade, and took the intersectionality of community, work, culture, and personal history to London Fashion Week with his show For the people who dream in colour. Rahman made every effort to stick with sustainable design and production principles. His textiles were made from cotton, wool, and silk and dyed naturally. The collection was produced with the collaborative efforts of Bangladeshi artisans at Aranya, a fair trade organization based in Dhaka.

Intersection and Expression: other creative acts

Rahman’s working practices incorporate what we at NKM love and cherish about our garments. But for Rahman, the full expression of what it means to have brown skin in post-colonial Britain, to be the son of immigrants, to be an openly gay Muslim, and to be mindful of the environmental and labor impact of the fashion industry doesn’t begin and end with a collection. Herein lies the dichotomy and dilemma for many designers. How does one align creative endeavors with sustainable practices? For Rahman, it means going beyond one single expression of the creative act.

There are a lot of sustainable designers in the world. And I could be doing other stuff that isn’t producing waste. It’s a tough conversation because if the aim of you making clothes is at the cost to communities like mine, or the black experience or from across Asia, surely there are other ways around it than creating these collections.

I get an overwhelming sense that for Rahman, fashion is but one form of creative expression. His latest endeavors go beyond sustainable design: with Lily Vetch he is co-directing and producing a documentary about Dhaka’s transgender community called Body of My Own.

We discussed the intersection of fashion and film and how these two mediums complement each other and can be used to tell stories and bring attention to social issues. Rahman sees this film project as a way to shed light on the experiences of the queer community in Bangladesh. In particular, he wants to discuss the experiences of trans women in Bengali society and the discrimination they face. The film gives voice to trans people – challenging stereotypes the broader culture has of them.

To be honest, it started off as a passion project. I thought it would be a short film, but now we’re four or five years in. And we now have a production company. We’re just watching this project grow because, in our head, because of how we’ve done the budget, it just means the bigger this film gets, the more money goes back to our collaborators [in the trans community].

So the bigger we can make this film, the more a genuine change that we can make for trans people by literally handing them the finances to do the things that they think are best for themselves. Whereas many others have received millions upon millions of pounds from the EU or the US to work within trans communities, nothing has changed for these people.

Changemaker: no fakery

Rahman asks the same question about community engagement projects on his home turf of East London where he is the Director of Training and Development at the British Bangladeshi Fashion Council.

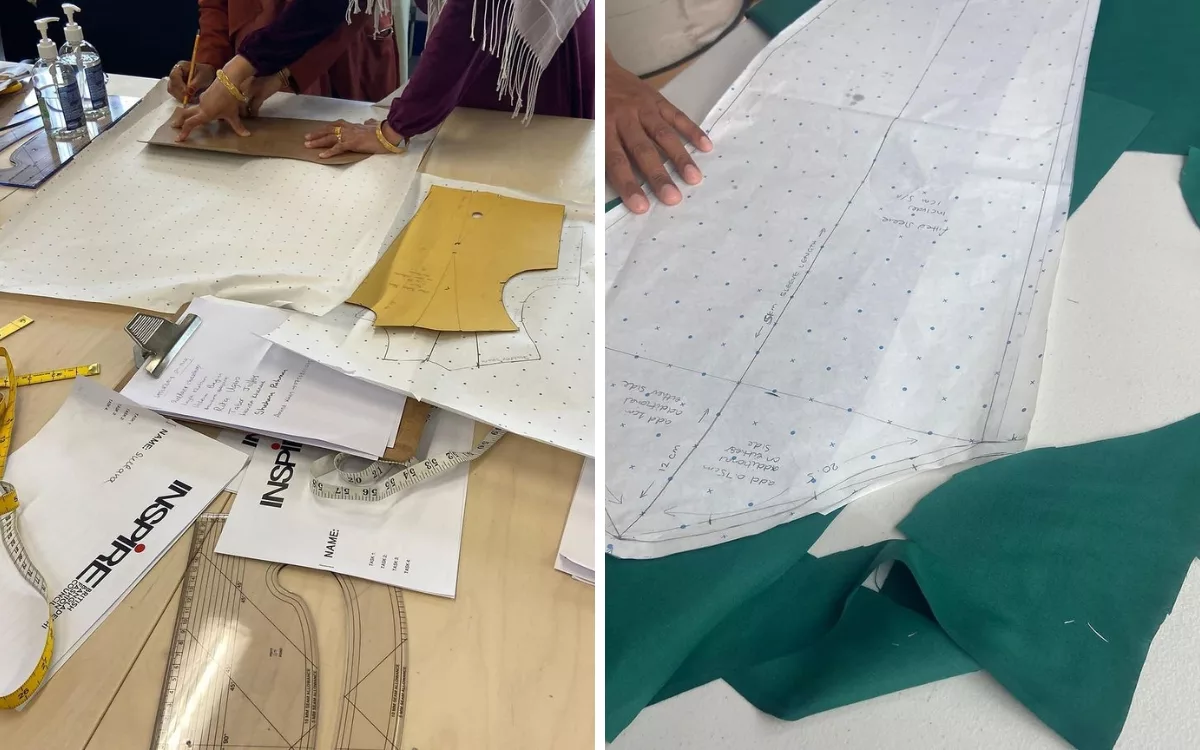

In his role at BBFC, Rahman’s developed a six-week creative community program for South Asian women, including skills development on the financial aspect of being a fashion entrepreneur.

Every program that I’ve seen targeted towards South Asian women is a “touch-and-go” type of project where the women come in, maybe make one bag, and then take the bag home. They’re not given any skills to be entrepreneurial, actual skills. I’ve started to embed this type of skills development into what I do.

Flow manifest: from the catwalk to the theatre.

Following in the steps of other fashion creatives like Hussain Chalayan, Christian LaCroix, and Gareth Pugh, Rahman is exploring initial forays into costume design. His first project is with Akademi, a South Asian dance group based in London.

A lot of the clients that I’ve worked with for fashion design stuff, like the stuff that you saw at the venue, everything was about a static garment. It actually wasn’t about movement.

And I wanted to see how my brain would react if I put movement into this – because the tailoring I was doing was about standing still. I wanted to see movement in design, to push myself to see if I could do that. And this is just the first one. So I’m still trying. I’ve got to keep playing.

After speaking with Rahman, I wonder if we are at a juncture in fashion and culture where creatives aren’t bound by one discipline or form of creative expression. We are entering a time when trying your hand at various fields to fully express your authentic self is perfectly legitimate. If one medium doesn’t quite work for you, surely another avenue exists. As design thinking becomes more steeped in the way we make products and do business, who’s to say that sustainable fashion design and ethical product design can’t be the springboard to other creative manifestations.

Rahman’s interdisciplinary practice challenges the idea of “staying in your lane” and refuses to be bound by one label. He is a filmmaker, a producer, an advisor and advocate. He’s a fashion designer, product designer and businessman. There isn’t one lane for Rahman, they’re all avenues for his creative vision.

Related Articles