A lot of Western media is biased towards west Africa – people talk about Nigeria, Ghana, and South Africa and nobody really talks about the rest of the continent. But we have fashion markets and creative economies in east, north, and central Africa as well, and I do think that it is important to highlight them.

Hadeel Osman, whose name has made the list of African Forbes 30 Under 30, and 100 most influential young Africans in 2020, is determined to reshape the world’s view on African fashion scenes –especially those that are more obscure. Her creative portfolio speaks volume for this determination. At just under 30, she is the creative director and founder of DAVU studio, Board member of the Union of Concerned Researchers in Fashion, Sudan’s Country Coordinator for Fashion Revolution, and a sustainable fashion consultant who is doing radio anchoring and DJ-ing.

To successfully leverage local African fashion, Hadeel believes in a two-pronged approach: creating more exposure for the continent’s fashion via engaging visual designs, along with advocating for less consumption of fast fashion and fashion waste among African consumers.

Below, we catch up with Hadeel on her journey in pushing for a better future for sustainable fashion in the continent.

Jacqueline/NKM: Hi Hadeel! It is an absolute pleasure to meet you today. Where are you based at the moment?

Hadeel Osman: Hi! Nice to meet you, too. I’m based in Sudan.

How many countries have you worked in and how many languages are you fluent in?

I’m fluent in Arabic and English and I’ve worked in, let me count… I think around five or six countries… The US, UAE, Sudan, Zimbabwe, Kenya. Five countries in total.

No wonder you lost count! Hadeel you are the most multidisciplinary creative I’ve ever come across. The number of projects that you’re currently involved in is just incredible. Correct me if I’m wrong –you’re a freelancer for Voice over artist, Radio presenter and anchor, Board member of the Union of Concerned Researchers in Fashion, and Sudan’s Country Coordinator for Fashion Revolution. Can you give us a walk through all your creative portfolio and tell us what is the one drive behind all of your work?

Sure! First of all, I performed all the roles that you’ve listed. AND I also own my studio called DAVU studio where I do most of my creative work.

Onto my creative journey. I started in visual communication and marketing in 2012 and I wanted to do something that kinda merges business with media. I just really enjoy doing visual work. I’m involved in a couple of projects and recently, as you mentioned, am also doing radio and voiceover work.

The main drive I have is that I got a lot of interest and I always want to try to explore each avenue and enhance my skills within each one.

That’s just amazing And you’re also the pioneer in sustainable fashion in Sudan. Okay, what was the moment that made you go: “ Aha, I’m going to embark on a career in sustainable fashion”?

Yes, that’s true. And that’s something that I’m very proud of to be honest.

I’ve been very interested in fashion since I was a child. I started thrifting 10 years ago and I came across Fashion Revolution Instagram page in 2015, when I first made an account. That was when I first learned about the harmful side of the fashion industry. I started learning more about it; naturally I began cutting down shopping from fast fashion brands. And it was quite easy because I didn’t come from the consumer’s mindset – even though I was brought up in the UAE, which was one of the wealthiest countries in the Arabian Gulf and their consumer habits are similar to the global north. But within our culture we were much more resourceful and we’re not materialistic, so it was easy to do.

Then on September 1st 2018 I decided to stop buying from fast fashion brands completely. And utilize what I have. I would upcycle, I would make something if I really needed it or I would shop second hand. Then I slowly started to shift the mindset of my family and my close friends.

In 2019 at the start of the pandemic I realized: “This is a good time to start discussing what’s happening because everything in the world is changing”. The rights of the people making these clothes were being violated, the orders were getting canceled, the workers were not getting paid… So that is when I actively campaigned and hosted Fashion Revolution in Sudan as well.

What an inspiring story. Hadeel, you’re also a researcher of the topic of the fashion resale market in Africa. Can you let us know the key differences between African resale market and that in America?

That’s a wonderful question. In America we see a lot of clothes being donated directly by the people, to charity for instance. But what we see in Africa is what we call waste colonialism. There are three big streams where these waste clothes are coming from: the big thrift stores and shops that have run out of space so they dump it here; the second is brands that have overstock or deadstock that cannot be sold because it’s way beyond the trend cycle; the last is reject clothing, they would rather sell it off to a warehouse –otherwise they would have to burn it. They are all waste and they are handed to us as if we were begging for it. It’s very offensive, I would say.

The damage is large-scale because it’s a proper trade. It’s not like when your average person in America donates clothes when it doesn’t fit you anymore or you don’t like it anymore. It’s a much bigger issue and it harms our local market, it harms our manufacturers.

Definitely an entirely different story compared to reselling clothes in America. So what is your view on it: should we ban it completely or should we still keep it but under certain regulations?

Bans alone cannot stop the problem. They have been issued before. For instance, in 2019, Uganda wanted to completely ban second hand clothes from entering the country: they pushed the “made in Uganda” campaign; they advocated people to have a local, regional, and international market. And then what they got was tariffs being imposed by the US, and sanctions being threatened. So even though African governments have been constantly trying to implement restrictions, we’re constantly met with threats which will impact our economy and our people.

Another reason why it should not be stopped immediately is because it’s not realistic. There are a lot of traders whose livelihoods depend on this. They buy used clothes in bulk and then sell them on the market or online. That’s their sole way of making money. To stop it immediately is going to negatively affect them.

That’s why there has to be regulations. But the countries that are dumping these clothes on the continent have to take accountability first. And the fashion companies that are making way, way more clothes than their actual target demographic can consume also need to reduce their production. So it has to start from the source, and the source is the government and the companies that come from foreign countries.

That is a poignant insight. People, when they donate clothes, think it’s a much more ethical option than throwing them to the landfill.

And the landfill becomes Africa!

That’s the side of the story people don’t know enough about. I’m glad you’re bringing this story to light. I want to touch on what you mentioned earlier about the clothes being out of the trend cycle. Does it reflect the fact that there is a mass consumer culture growing in Sudan and in Africa? What is the socio-economic state of African youth?

I’ll speak on Sudan first, and then I’ll expand. Sudan, in comparison to other African countries, has a lot of economic and political issues, so the way things are set up for us is vastly different. In Sudan, there are a lot of youths, and they are in tune with trends. They want to look good and they want to dress themselves –which they deserve to. But there are very limited financial resources for them to be able to do that.

Sudanese consumerism is also increasing. Even though we are a sanctioned country with no Zara or H&M stores around the corner, what you can find is people who buy fast fashion in bulk, from another country (usually the UAE), and then sell it in boutiques. Also, Shein has taken over the market; because they sell it online, no brick-and-mortar establishment is needed. Both Shein and imported fast fashion are cool, new, trendy, and most importantly cheap, so they meet the demand of the local youth to purchase as many fashion items as possible within a limited budget. Also there’s this constant pressure for women not to repeat their outfits –that they have to wear something new, especially for big occasions. This is due to persisting outdated beliefs in our culture, which emphasize that women have to look good all the time in order to get married.

So, inevitably, consumerism is growing.

In East Africa and other parts of Africa, based on my travel, my reading, and my research as well, people make use of the secondhand market more. Because it makes economic sense. In other African regions, second hand clothes are more affordable, more accessible, and there are more options to choose from. We do have a secondhand market in Sudan, but because of the economic situation, used clothes prices are so high that customers prefer buying something new rather than spending hours searching for a second hand item in a market under the sun.

However, secondhand consumption does harm the local market in these parts of Africa. Cheap secondhand competes with much more costly local designs. Local designer clothes are more expensive because you’re paying for the craftsmanship, the textile, and the time taken.

In the recent decade, African fashion has received much more recognition. Nigerian fashion for instance. Why do you think we have yet to leverage the artistry and the culture in Sudan to make it a more prominent player in the global fashion stage?

I think the main reason is that a lot of Western media is focused on West Africa. I remember people used to only talk about Nigeria, Ghana, and South Africa and never talk about the rest of the continent. Also these countries have rising economies, they’re more established, and they don’t have as many issues with foreign media as other African countries. So they are more well-known, not just for fashion. But I do think that it is important to highlight East, North, and Central African as well, because we do have markets that come from these places in Africa, like you just said.

So with all that said, in your opinion, what are the best practices to do slow fashion in Africa? What is a compact guide for a Sudanese or an African when they decide to be more intentional with their fashion purchases?

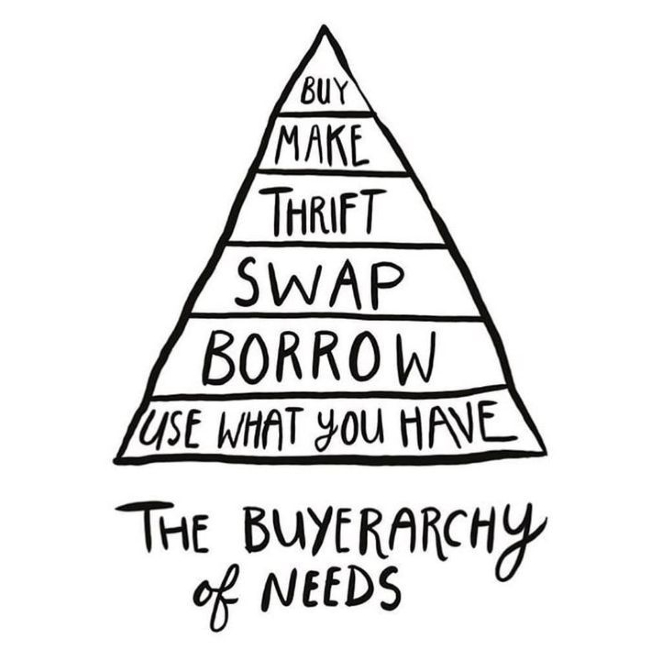

My guide would be based on this hierarchy of needs, where “using what you have” is the first priority and “buying new” should be the absolute last option. It kind of mimics Maslow’s hierarchy of needs.

I recommend:

- First, organize what you have. Do a wardrobe audit. That way you know exactly what you own because sometimes we have things at the back of a closet that we forget. Look at what you have and try to style them – be imaginative, take the time to create different looks!

- So let’s say after you’ve done that you still feel like you need to buy something because there’s something missing in your wardrobe. Consider borrowing from a relative or a friend, or swapping – which means you exchange something you don’t really love anymore for something someone in your circle has and they also don’t want it. That way you both are not attaining new because you’re replacing it instantly.

- Another option would be to make it. We have a decent sized textile market across the continent, some of them are locally manufactured, some of them are imported into the country. But in all cases you can make something new. Also you’re supporting the local fashion workers – whether it’s a local seamstress, a local tailor, or even a local independent designer. You’re assisting them in making a living; plus the clothes are going to be unique and made exactly for your body shape.

- And then there is a case of secondhand. You can tailor it if you want to personalize it a little bit more. Again you’re helping the local trader because you’re buying from them, but you’re also helping the local seamstress or the tailor who is going to adjust or upcycle what you have.

- The last option should be buying new. And by new, it can be something that comes from China, or something from fast fashion brands.

So that’s my guide and that’s the way I go about things as well.

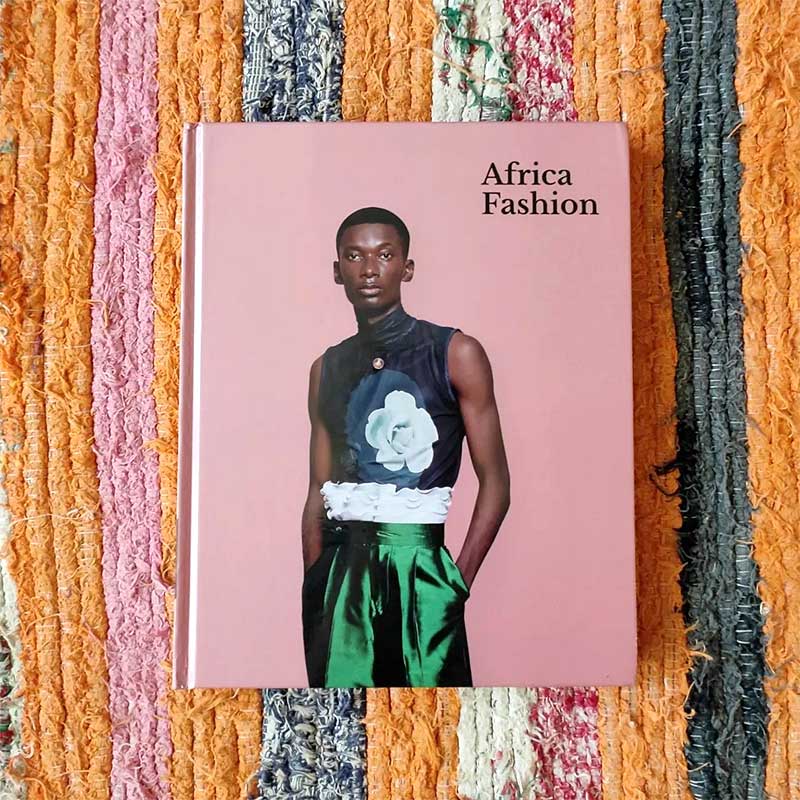

You had an essay about secondhand fashion published in the Africa Fashion book that’s part of the exhibit in London. Can you share with us how that happened?

I was contacted back in October 2020 by the V&A team exhibition curators and was involved in several discussions with African based, diaspora and fashion experts the world over, then I was given the incredible opportunity to write for the exhibition book. It was a no-brainer to choose a topic that revolved around second hand markets in the continent and to have an overview piece that dissects the main components of this part of the fashion supply chain that is often forgotten and neglected. I’m forever grateful for this opportunity and it further cements my desire to continue working and expanding in the African fashion industry.

I’d like to touch on this issue of gender inequality in Sudan. I’ve read that Sudanese women are seriously maltreated and they are under so many unjust restrictions. Does that impede the professional growth of Sudanese female creatives?

Yes. Definitely. We had a very strict and damaging regime that took over around 30 years ago. What they wanted to do was to change our society. A lot of it was to break peoples spirit down and make us become followers of orders. In a way it was an entire dictatorship.

Under this dictatorship, it was very hard to navigate life as a woman living at that time. Women had a very, very long, rough time. We were not able to dress how we like. There’s this thing called social order police: if, let’s say, a girl was wearing pants, and the officer felt like he could arrest her, he could legally do that. And he actually would. There are so many infamous cases that you can easily find online.

Then came the December Revolution in 2018 and 2019. We were able to oust the president who was ruling for 30 years with his regime, back in April 2019. And some change started to happen. Women started getting more recognition. Their voices were being heard, and there were a lot of activists that were able to reach even more of an audience. They still were working back then in terms of helping with women’s rights, but they just had even more of a platform now. Because the whole country was against this regime that really stifled us, our economy and our regional, and international relationships.

So there was a lot of improvement, and a lot of hope for the entire country in all aspects, especially for women. And during that time there was this rebirth of the understanding and recognition of creatives, especially female creatives. Because they have this new platform where they, though not yet considered equals, were seen, heard, and appreciated. And I said rebirth because in Nubian ancient traditions, the women are well respected. The Nubian queens were ruling the area at that time and they were called Kandaka. So during those two years, Sudanese women were addressed as Kandaka, as queens, as people with authority that should be listened to and respected.

That went on for 2 years, up until October of 2021. On October 25th there was a military coup. And unfortunately now, things have gone downhill again.

Our country is falling apart. I myself am considering leaving the country for good very soon, along with many creatives. I’ll probably be leaving in two months. So a lot of people are relocating and migrating because we cannot live, it’s not safe. And also we cannot do what we want. Even in our field, financially it doesn’t make sense.

To sum it all up, I would like to say that there was improvement in terms of women’s rights. Right now, even with all that’s happening, society looks at women a bit better than it did before. There was a little bit of improvement, very small bit improvement, which is something that we should be proud of. But we have so, so, so long to go, a very long time until women can get equity in treatment, and have the ability to live as they should and as they deserve.

Such a shame. I never thought everyone was leaving – I was going to ask you how fashion can play a role in the empowerment of women. But under such an unstable climate, I guess it’s still far-fetched. Truly heart-breaking

It really is. There are still people and women working in the creative industry and starting businesses as creative entrepreneurs, as photographers, as designers, as we’re talking about fashion. There are more designers coming up every single day. I wouldn’t call it an industry just yet because most of them are working individually or partner with a tailor or they would try to have a small team but it would always be on the smallest scale. But still I am very proud of how they were still able to push forward and being able to sell and have their business running.

There are also fashion hubs opening, where they try to teach people how to make clothes. There are workshops available, but everything comes at a price. So it just depends on where the person is located and what they can afford in order to make it a sustainable business. But even the independent designers that have reached household name status, cannot run their fashion business full-time. I myself have wanted to make clothes for a very long time but have only started now, and I am doing them all by myself. And I’m doing it on a very small scale kind of fashion just to understand the market. Hopefully when I’m in a better place, I could have a full-fledged brand.

Nevertheless I think it’s just incredible what you’ve gone through to get to where you are today. I would be curious to know if you could share with us a memorable challenge that really shaped you into who you are today, Hadeel

Oh that is a tough question. I think one of the biggest challenges was the decision I made back in 2018 when I decided that I would relocate and make Sudan my base. I came here in January and I decided this is where I’m going to be based, this is where I’m gonna call home. Yes, I was traveling a lot for the past four years, but it was a lot to get used to. I came from a background where I was allowed to be creative, I was allowed to express myself, to dress how I want, to make decisions appropriately as an adult. So coming to Sudan I had to learn how to make decisions that would make me look good and would not harm me from a societal point of view. I had to change the way I dress, change how I speak –I had to try to find my people which was very hard. And the way that businesses are run here is very different compared to the UAE or the USA. So having to adapt is a huge, huge challenge for me but it was something that I was very grateful for because now, whenever I go to a more established place, like anything that comes my way is a minor inconvenience because here, I have to deal with power cuts, and water cuts, and Internet blackouts, complete telecommunication blackouts, arrests on the street. So when I go somewhere and something goes wrong, I easily have solutions because it’s not that bad.

Such a powerful tool kit. What doesn’t kill you, truly makes you stronger. Personal question, who or what inspires you and keeps you looking forward to doing the work that you do?

I am very passionate about the journey of each product that I do. I really like the process from start to finish, the struggle to find solutions, the whole process of creating a concept. So that’s what keeps me going. Also the sharing of knowledge and the job opportunities that I can create for others. People look up to me, which is a huge honor. If I can show them how it can be done, that way we are encouraging each other to improve collectively. So that’s the thing that really, really makes me want to keep going. Because I’m not the only one who is benefiting, someone else is also benefiting by proxy regardless of how close they are to you.

What is next for you?

I’m really working towards creating a fashion brand that is “self maintaining”, I want to say. So, upcycling of goods, using deadstock fabrics. That’s one thing. I really want to continue working on my research, I really want to expand my network, getting into sustainable fashion consulting small, medium, and large brands. Ideally I really want to be one of the people that changes the view of the African fashion scene globally. And hopefully changes the way fast fashion brands operate. To have a true impact so that sustainability would not just be a catchphrase, to remove greenwashing and actually get the real work done.

Follow Hadeel Osman on: IG // DAVU Studio Webpage

–Jacqueline Pham

Related Articles

Culture Dose | AFRICA + FASHION

What To Do With Old Clothes Instead of Donating to a Thrift Store

Thebe Magugu A/W 2020

Our Favorites from Paris Fashion Week

Donating to a Thrift Store? Read this First

One to Watch: Abiola Onabulé The London designer who brings Nigerian heritage to fashion

Redress Design Award Winner Le Ngoc Ha Thu