Back in 2016, millennial pink dominated the discourse. Every YouTuber prayed at the altar of Glossier and Reformation. All the #girlbosses ceremoniously sang The Wing’s praises. Made by women for women was the common refrain.

Instagram-friendly, for-profit feminism was in – until its true nature as an artfully packaged, exclusionary cult was uncovered. Reformation and Glossier had racist CEOs, more Ms. Hyde than Jekyll. These brands were made-to-order – ultimately by and for white gentrifiers.

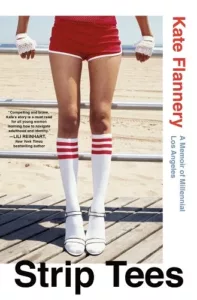

I was reminded of this duplicity while reading Strip Tees: A Memoir of Millenial Los Angeles, Kate Flannery’s memoir of her time at Dov Charney’s American Apparel.

For socially conscious shoppers, American Apparel offered a refreshing approach: “Everything produced in the Factory was made by fair-wage workers, garments you could feel good about wearing and selling.” Or, as Ivy, the young woman who recruits Flannery, notes, “Not like that Forever 21 fast-fashion garbage, made in sweatshops overseas… He [Founder Dov] knows you don’t have to stand on people’s necks to make a profit.” By situating his brand in the labor rights debate, Dov created an “us versus them” narrative that made shopping at American Apparel a morally superior choice.

Most importantly, it claimed to uplift and celebrate female employees. Even when these female employees served as models for the brands soft-core porn aesthetic. When recruited to join, Flannery initially protests that she is not a model but a feminist. Ivy laughs and replies, “You can be both, you know.”

In the early 2000s, when fashion and fun-loving figures like Paris Hilton were dismissed for their perceived lack of intelligence, American Apparel claimed to value workers for their looks and intellect. A woman could party with her girlfriends and pose in a sexually provocative way and emerge as a leader. In this light, the controversial ads were framed as a symbol of female agency.

In actuality, the supposedly progressive Dov was exploiting his employee base. True, most companies are guilty of perpetrating a hustle-and-grind culture to some extent, but Dov’s offering was uniquely nefarious. This CEO didn’t stand on his workers’ necks when he could break them, unquestionably abusing workers in perceived service to the brand.

This reality was a far cry from the pitch Flannery received when joining: “We’re a family here. Everyone works together for a common goal – to make the world a better place.”

Sure, if your model for healthy family life is Succession.

Moreover, when business wasn’t going well, Dov rendered American Apparel positively dystopian, blaming employees for his poor business decisions. He even punched one employee in the stomach to resolve a dispute. From Dov’s perspective, workers like Flannery were first and foremost expendable resources.

A culture of toxic sexual mind games

In the book Flannery shares that they hired workers he was personally attracted to that fit his “girl next door” archetype. From there, the “Dov’s Girls” employees were expected to have sex with him if they wanted to advance their careers. The glimpses of male anatomy in candid photo shoots were his. The photo shoots became ads that were candids of his sex life…with employees half his age. Knowing this, the ads today read more Jeffrey Epstein than Calvin Klein.

The Victim

To Dov’s apparent villain, Flannery portrays herself as the victim. She claims she drank the Kool-Aid and bought Dov’s messaging for so long because she didn’t know any better. Inherent to her narrative is the belief that she was taken advantage of – which Flannery unquestionably was. Though not one of his sex toys, she was subject to his deranged verbal tirades and suffered severe sexual harassment by male employees. She also feared the economic consequences of leaving American Apparel.

Women don’t have to be the ‘perfect victim’ to suffer the realities of abuse. Yet while Dov’s cult may have victimized her, no one forced Flannery to remain.

Unlike most employees, she joined American Apparel as an upper-middle-class, Ivy League-educated woman approaching her mid-twenties. She clearly states that American Apparel initially appealed to her feminist identity. Given this fact – she takes pride in one memory of Gloria Steinem speaking at her school – it is hard to believe her critical thinking facilities were so stunted as to buy into Dov’s ethos.

And they weren’t. Flannery quickly recognized the wrongness of the situation. Part of what makes the memoir compulsively readable is its gossipy quality – a never-ending parade of judgment in sordid detail after detail. Whether hearing Dov’s Girls baby talk to him over the phone or refer to an Asian woman as Dov’s “geisha,” she is quick to voice how as a feminist, she recognized that this behavior was appalling.

Still, she never took action or spoke up about abuses. And she didn’t leave. I kept waiting for her to go, but page after page, year after year, abuse after abuse, she felt compelled to stay until the brand collapsed under the weight of Dov’s egotistical transgressions.

Flannery’s feminist/victim stance becomes less convincing chapter by chapter. So why does she stay? She stays at American Apparel because the culture, albeit toxic, is fun. So much for feminism when you can go to parties.

Within Flannery’s narrative, her supposed victimhood discounts her role as an active participant in the toxic sexual culture. Her noted value is her ability to find girls with the innocent All-American qualities Dov finds attractive and manipulate them into joining the company.

From my perspective, these young women were the primary victims – they didn’t have the same educational tools or resources Flannery had. If he reads like Jeffrey Epstein, then Flannery is his Ghislane Maxwell. (granted not to the same extreme but you get it…)

In this situation and later when she deals with personal harassment, Flannery dutifully frets and complains, yet promptly waives her legal rights when Dov offers to buy her a lovely apartment.

Given her complacency and knowing contribution to the toxic culture, Flannery’s motivation for writing this memoir seems suspect. Did she write it to expose Dov’s abuses from an insider’s point of view? Or to evade culpability by painting herself as a naive feminist led astray? By situating her story in the context of #MeToo, I suspect a bit of both.

I appreciate Strip Tees as a pulpy, narrative. I’ll even recommend you read it as a cautionary tale. But don’t buy the book’s blurb, where “Hunter S. Thompson meets Gloria Steinem.”

Comparing the passively duplicitous narrator to a courageous gonzo journalist and a feminist who transgressed the patriarchal status quo is laughable. It’s more like an early 2000s Bret Easton Ellis.

Yet Flannery’s entertaining narrative is like American Apparel itself. Deliciously provocative but with a questionable aftertaste. Strip Tees reflects the very problems it’s pretending to expose: what happens when exploitation poses behind a progressive veneer.

There’s also a troubling epilogue. While we celebrate this seemingly candid narrative, what Flannery fails to mention is Dov’s continued trajectory in the fashion industry. In 2016, he launched Los Angeles Apparel and has collaborated with Ye to make “White Lives Matter” shirts – simultaneously stating that “ethicality and humanness are themes congruent to Los Angeles Apparel’s success.” Considering the prolonged hypocrisy Flannery’s memoir overlooks, it is evident that when weighed against financial success, ethics in the LA fashion world are still worth Less than Zero.

–Jayna Rohslau

Related Articles